ΑΙhub.org

Are sixteen heads really better than one?

By Paul Michel

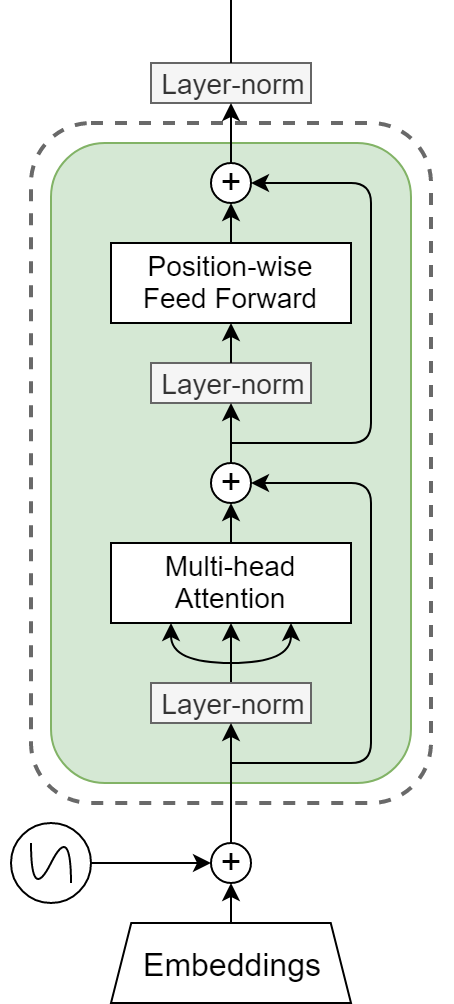

Since their inception in this 2017 paper by Vaswani et al., transformer models have become a staple of NLP research. They are used in machine translation, language modeling, and in general in most recent state-of-the-art pretrained models (Devlin et al. (2018), Radford et al. (2018), Yang et al. (2019), Liu et al. (2019) among many, many others). A typical transformer architecture consists of stacked blocks, one of which is visualized in Figure 1. Such a block consists of a multi-head attention layer and a position-wise 2-layer feed-forward network, intertwined with residual connections and layer-normalization. The ubiquitous use of multi-headed attention mechanism is arguably the central innovation in the transformer. In this blog post, we’ll take a closer look at this multi-headed attention mechanism to try to understand just how important multiple heads actually are. This post is based on our recent NeurIPS paper.

Multi-headed Attention

Before delving into multi-headed attention, let’s first discuss regular attention. In the context of natural language processing (NLP), attention generally refers to a layer computing a content-based convex combination of a sequence of vectors. This means that the weights themselves are a function of the inputs, with a common implementation being:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} \text{Att}_{W_k, W_q, W_v, W_o}(\textbf{x}, q)&=W_o\sum_{i=1}^n\alpha_iW_vx_i\\ \text{where }\alpha_i&=\text{softmax}\left(\frac{q^{\intercal}W_q^{\intercal}W_kx_i}{\sqrt{d}}\right)\\ \end{split}\]](https://aihub.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-e41d0f59ff1a7354a1d972d8ceb56ddc_l3.png)

With parameters ![]() , input sequence

, input sequence ![]() and query vector

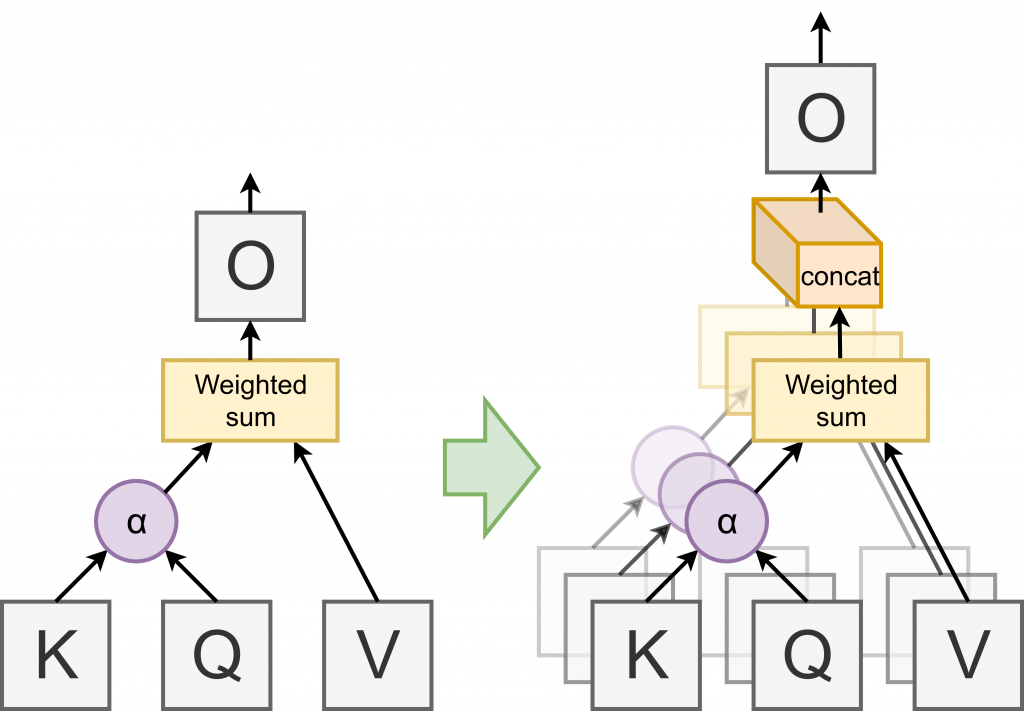

and query vector ![]() . There are a variety of advantages tied to using attention instead of other sentence pooling operators such as recurrent neural networks, not the least of which being computational efficiency in a highly parallel environment (such as a GPU). However, they do come at the cost of expressivity (for instance attention can only take values in the convex hull of its inputs). The solution proposed in Vaswani et al. was to use “multi-headed attention”: essentially running

. There are a variety of advantages tied to using attention instead of other sentence pooling operators such as recurrent neural networks, not the least of which being computational efficiency in a highly parallel environment (such as a GPU). However, they do come at the cost of expressivity (for instance attention can only take values in the convex hull of its inputs). The solution proposed in Vaswani et al. was to use “multi-headed attention”: essentially running ![]() attention layers (“heads”) in parallel, concatenating their output and feeding it through an affine transform.

attention layers (“heads”) in parallel, concatenating their output and feeding it through an affine transform.

By splitting the final output layer into ![]() equally sized layers, the multi-head attention mechanism can be rewritten as:

equally sized layers, the multi-head attention mechanism can be rewritten as:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} \text{MHAtt}(\textbf{x}, q)&=\sum_{h=1}^{N_h}\text{Att}_{W^h_k, W^h_q, W^{h}_v,W^h_o}(\textbf{x}, q)\ \end{split}\]](https://aihub.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-108cf36e095110dfa56c4bfd51152e20_l3.png)

With parameters ![]() and

and ![]() . When

. When ![]() , this formulation is strictly more expressive than vanilla attention. However, to keep the number of parameters constant,

, this formulation is strictly more expressive than vanilla attention. However, to keep the number of parameters constant, ![]() is typically set to

is typically set to ![]() , in which case multi-head attention can be seen as an ensemble of low-rank vanilla attention layers.

, in which case multi-head attention can be seen as an ensemble of low-rank vanilla attention layers.

Cutting Heads Off

But why are multiple heads better than one? When we set out to try to answer that question, our first experiment was the following: let us take a good, state-of-the-art transformer model and just remove attention heads and see what happens. Specifically we mask out attention heads at inference time by modifying the expression for the multi-head layer with:

![Rendered by QuickLaTeX.com \[\begin{split} \text{MHAtt}(\textbf{x}, q)&=\sum_{h=1}^{N_h}{\xi_{h}}\text{Att}_{W^h_k, W^h_q, W^{h}_v,W^h_o}(\textbf{x}, q)\ \end{split}\]](https://aihub.org/wp-content/ql-cache/quicklatex.com-afd4141a5ac54fcc56e738e40b6299fe_l3.png)

Where ![]() is the

is the ![]() -valued mask associated with head

-valued mask associated with head ![]() .

.

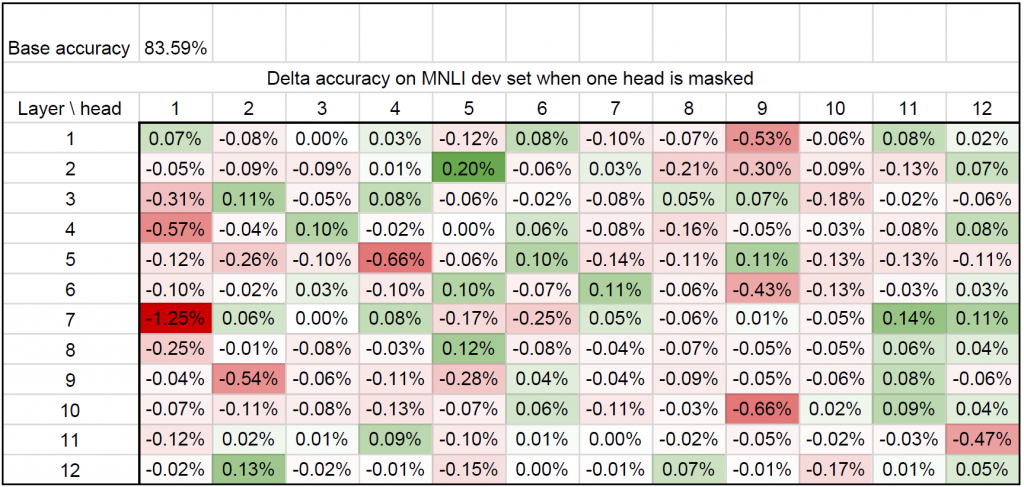

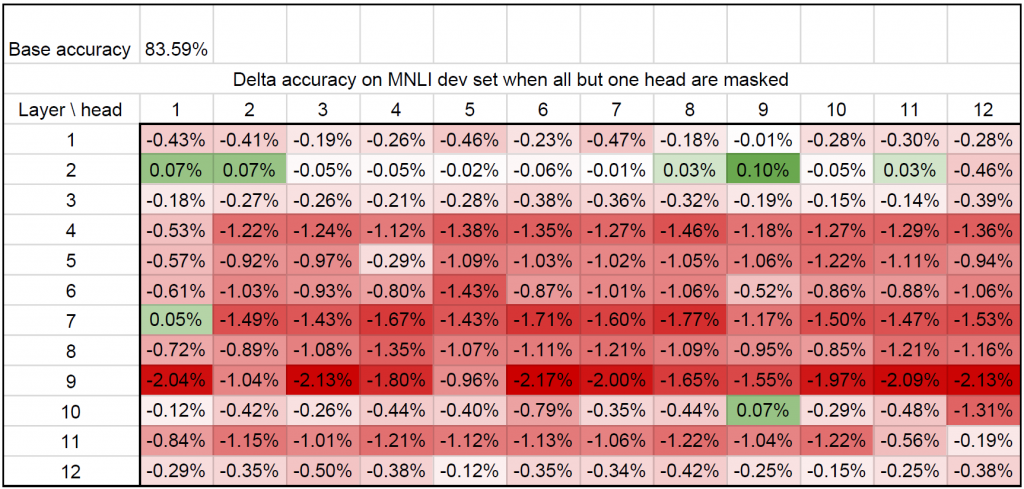

We ran our initial experiments with a BERT model (Devlin et al. 2018), fine-tuned on the MultiNLI dataset (a dataset for recognizing textual entailment). We exhaustively pruned each attention head independently and reported the difference in BLEU score (a standard MT evaluation metric) in a spreadsheet. To our surprise, very few attention heads had any actual effect (see Fig. 3).

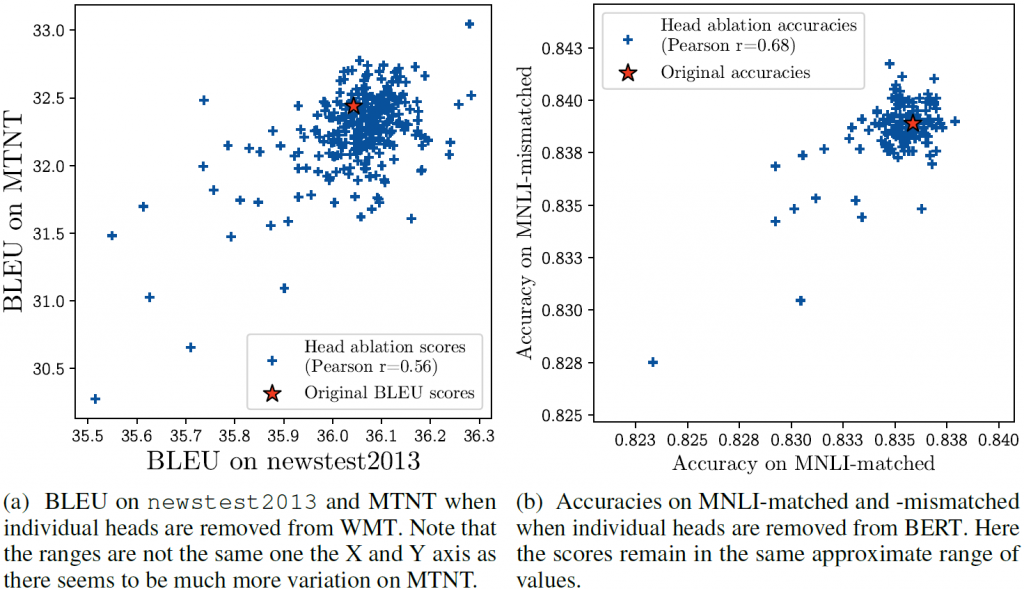

This suggested to us that most heads were actually redundant. We additionally tested how the impact of ablating particular heads generalizes across different datasets that correspond to the same task. For this, we looked at two tasks with two corresponding datasets: machine translation (datasets: newstest2013 (news articles) and MTNT (Reddit comments)) and MultiNLI (datasets: matched and mis-matched). Interestingly, this phenomenon generalizes across domains within a certain task, as evidenced in Figure 4: there is a positive linear correlation between the impact of removing each head on different datasets.

To push this point even further, and take a jab at the titular question, we reiterated the experiment with a twist. For each head, we computed the difference in test score after all other heads in this multi-head attention layer are removed (keeping the rest of the model the same — in particular we don’t touch the other attention layers).

It is particularly striking that in a few layers (2, 3 and 10), some heads are sufficient, ie. it is possible to retain the same (or a better) level of performance with only one head. So yes, in some cases, sixteen heads (well, here twelve) are not necessarily better than one. However these observation don’t address two key issues:

- Compounding effect of pruning heads across the model: we are considering each layer in isolation (we are keeping all heads in the other layers), however removing heads across the entire transformer architecture is likely to have a compounding effect on performance

- Predicting head performance: we are observing the effects of head ablation in hindsight on the test set.

Systematic Head Pruning

To address these issues, we turned to the various approaches explored in the pruning literature to compute an importance score ![]() , estimated on a validation set or a subset of the training data, to be used as a proxy for determining the order in which to prune heads. A low importance score

, estimated on a validation set or a subset of the training data, to be used as a proxy for determining the order in which to prune heads. A low importance score ![]() means that head

means that head ![]() will be pruned first. Specifically we set

will be pruned first. Specifically we set ![]() to be the expected absolute difference in loss before (

to be the expected absolute difference in loss before (![]() ) and after (

) and after (![]() ) the head

) the head ![]() is pruned:

is pruned:

![]()

(J.B. Louvion, 18th century; source: BnF)

We approximate this difference at the first order, which makes it possible to compute ![]() for each head with a single forward and backward pass over each sample in dataset

for each head with a single forward and backward pass over each sample in dataset ![]() . Otherwise we would have needed as many forward passes as there were heads in the model (plus one for the un-pruned model). For models such as BERT (

. Otherwise we would have needed as many forward passes as there were heads in the model (plus one for the un-pruned model). For models such as BERT (![]() heads) or big transformers for translation (

heads) or big transformers for translation (![]() heads), this is highly impractical. On the other hand, using this rough approximation we can compute all

heads), this is highly impractical. On the other hand, using this rough approximation we can compute all ![]() simultaneously, and the whole process is not anymore computationally expensive than regular training.

simultaneously, and the whole process is not anymore computationally expensive than regular training.

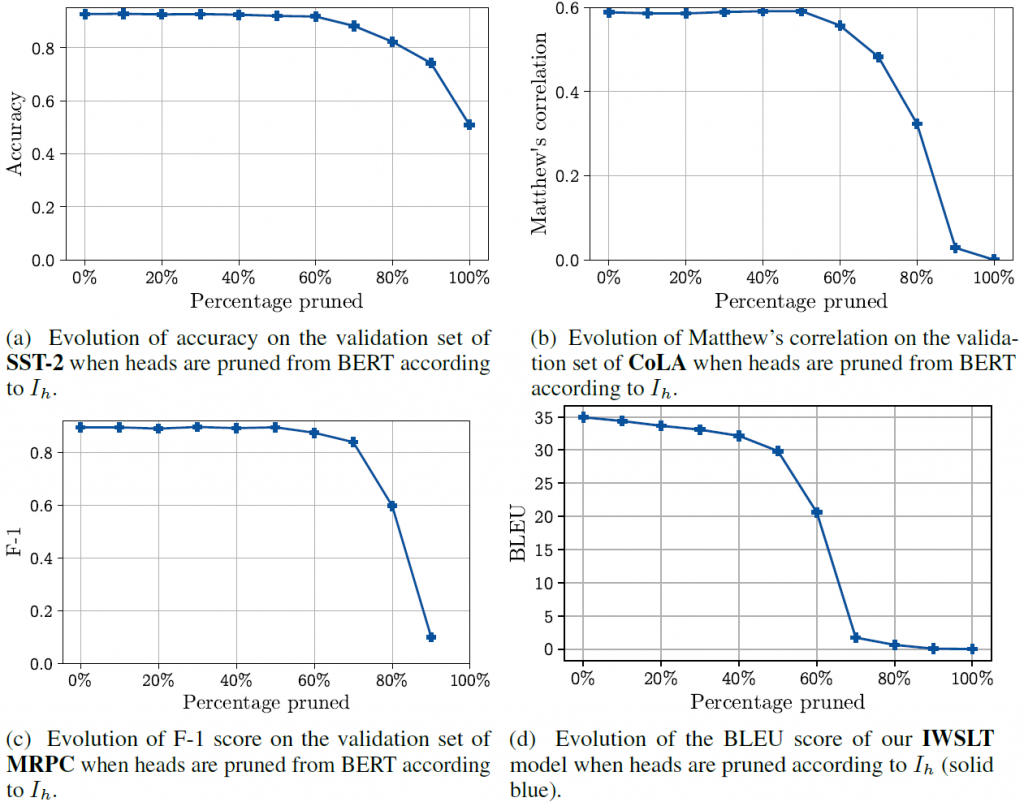

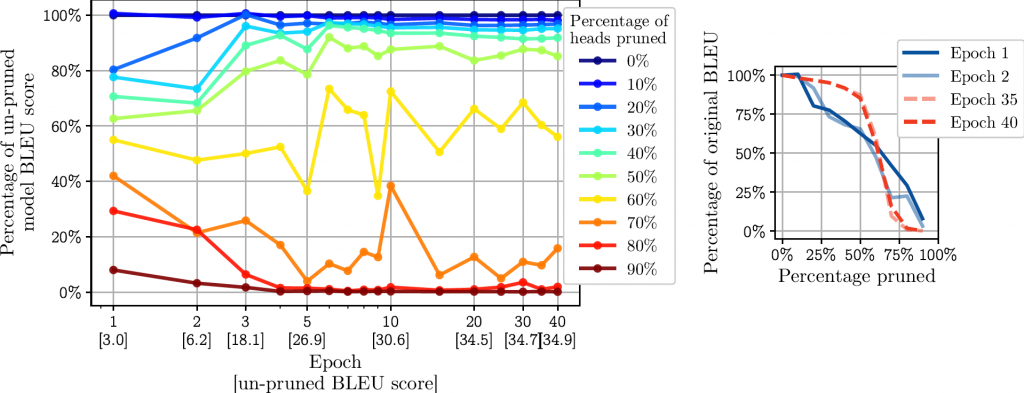

In the figure below, you can see the impact of systematic head pruning on performance on a variety of tasks. Here we prune the heads in order of importance, ie. “10% pruned” means we pruned the heads with the 10% lowest ![]() , etc.

, etc.

So the picture is a bit more nuanced here. On one hand it is possible to reduce the number of heads by up to 60% without any loss in performance depending on the task and the model. On the other hand we aren’t able to go down to one head per layer either. So in general, multiple heads are better than one.

What Happens during Training?

One of the things we wondered about was at what point during training time does this phenomenon arise. We investigated this by pruning a model at different stages of the optimization process using the method described above. For this experiment, we used a smaller transformer model for German to English translation (6 layers and 8 attention heads) trained on the IWSLT dataset. We looked at how the “pruning profile” — the rate at which performance decreases as a function of the pruning percentage — changes over the course of optimization.

During the first few epochs, the pruning profile is linear, which suggests that all heads are equally important (pruning 10% of the heads costs ~10% of the model performance). However, notice the concentration around the uppermost (close to 100% of the original score) and lowermost (close to 0% of the original score) portions of the graph that starts to appear as early as epoch 3. This indicates that early in training, a clear distinction develops between redundant heads (40% can be pruned for a ~10% cost in performance) and “useful” heads.

Would you Like to Know More?

A handful of work was published around the same time as our own trying to understand the role of self-attention in transformer models. Two particularly interesting starting points are:

- Analyzing Multi-Head Self-Attention: Specialized Heads Do the Heavy Lifting, the Rest Can Be Pruned (Voita et al. 2019): this paper focuses on the self attention layers in machine translation models. They identify the “roles” of some attention heads (whether the head attends to rare words, or coincides with dependency arcs, etc…) and develop a smart head pruning algorithm.

- What Does BERT Look At? An Analysis of BERT’s Attention (Clark et al. 2019). This paper’s analysis is centered on BERT (Devlin et al., 2018), the at-the-time de facto pre-trained language model. The authors go really in-depth in trying to understand the role of attention heads, especially looking at which syntactic features can be retrieved from self-attention weights.

If you’re looking for a more general overview of the work that has gone into understanding what large scale transformer language models are learning, this recent paper provides an exhaustive review of the current state of the literature: A Primer in BERTology (Rogers et al. 2020).

What’s Next?

So as it turns out while sixteen heads *are* better than one at training time, a lot of heads end up being redundant at test time. This opens up a lot of opportunities for downsizing these humongous models for inference (and in fact a lot of recent work has gone into pruning or distilling big transformer models, see e.g. Sanh et al., 2019 or Murray et al., 2019).

One aspect I’m particularly interested in is leveraging this “excess of capacity” to tackle multi-task problems: instead of discarding these redundant heads, can we use them more efficiently to “cram more knowledge” into the model?

The work in this blog post was originally published as a conference paper at NeurIPS 2019 under the title: Are Sixteen Heads Really Better than One? (Michel et al. 2019).

DISCLAIMER: All opinions expressed in this post are those of the author and do not represent the views of CMU.

This article was initially published on the ML@CMU blog and appears here with the author’s permission.