ΑΙhub.org

From Visual Question Answering to multimodal learning: an interview with Aishwarya Agrawal

In the latest issue of AI Matters, a publication of ACM SIGAI, Ella Scallan caught up with Aishwarya Agrawal to find out more about her research, what most excites her about the future of AI, and advice for early career researchers.

You were awarded an Honourable Mention for the 2019 AAAI / ACM SIGAI Doctoral Dissertation Award. What was the topic of your dissertation research, and what were the main contributions or findings?

My PhD dissertation was on the topic of Visual Question Answering, called VQA. We proposed the task of open-ended and free-form VQA – a new way to benchmark computer vision models by asking them questions about images. We curated a large-scale dataset for researchers to train and test their models on this task. In this task, we show the models images from the dataset, and we test the understanding of these models by asking them questions – just like how you would test a child’s understanding of a particular subject.

This task was quite new 10 years ago. In computer vision in 2015, people were evaluating models using bucketed recognition tasks like image classification. You would train the model on a limited set of categories and ask it to classify dogs, cats and things like that. We were not quite happy with that kind of model evaluation, because in that setup, the model can only learn the categories you specify. We felt this wasn’t suitable for the medium of interaction. Let’s say, if I am blind and need visual assistance, my interactions would not be limited to a few categories – I would want to be able to interact with these systems in free-form natural language. This led to us proposing the VQA dataset to train computer vision models.

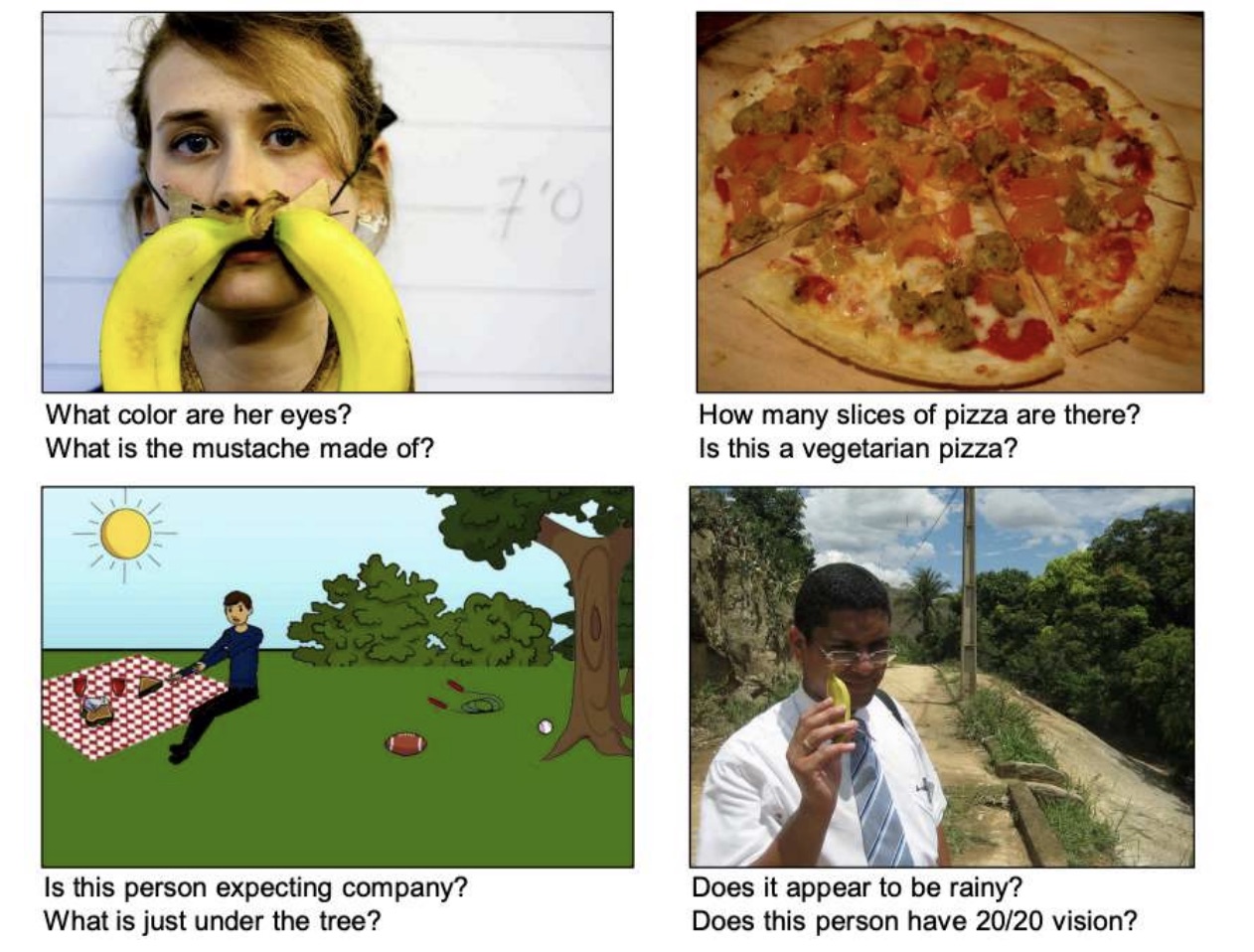

Examples from the VQA dataset. Image credits: Agrawal, A., 2019. Visual question answering and beyond. PhD Dissertation. Georgia Institute of Technology.

Examples from the VQA dataset. Image credits: Agrawal, A., 2019. Visual question answering and beyond. PhD Dissertation. Georgia Institute of Technology.

After we published this dataset, many people in the computer vision community started using it to build models. We knew that they were performing similarly in terms of their average performance, but I was curious to understand them better. I wrote a paper where we proposed a few methods to characterize the behavior of these models, to try and understand where they are failing, what their weaknesses and strengths are, and so on. Later on, contributed some methodological changes to improve the models on a particular weakness which was quite prevalent at that time: they wouldn’t pay attention to the content of the image, and they would make predictions biased by language biases in the dataset. I proposed novel architectures, objective functions, and evaluation protocols to try to help tackle that problem.

Interesting, it sounds like you covered a lot of ground. How has your research developed since then?

It’s been 10 years, and I still work on vision and language. I’ve expanded the scope of my research beyond the specific problem of VQA to cover other vision and language problems.

Over the last 10 years, there has been a lot of progress in the community in terms of the capabilities of these models – they are much stronger these days compared to how they used to be. I’ve seen this quantitatively – during my PhD, we used to organize annual VQA workshops at CVPR, which is a premium Computer Vision Conference. As part of that, we would organize annual competitions where we would evaluate state-of-the-art models on the VQA dataset, and the performance on that task has improved quite significantly – by ~25% over the last 10 years. This is very concrete evidence of how much progress we have made in the community since then. Many of the low hanging problems that used to exist 5/10 years ago are now solved, but now there are new questions, questions that we wouldn’t have even thought of 10 years ago when the models were not good at basic perception skills.

Now that these skills have been mastered, we are thinking about bigger questions. For example, how do we make these models work across cultures? How do we align these models with diverse cultural expectations? The success of the latest models depends heavily on the size of the training data – millions and billions – which makes it difficult for us in academia to develop such models. Can we make them more data efficient, and if so, how can we smartly select the most effective data points to train these models on? There are also some very fundamental questions. How do we learn visual representations that are compatible with language, given that vision and language are two very different modalities. So these are some open research questions in vision language. I’m working on those, but I’m also expanding my horizons to embodied Al, multi-agent settings etc.

Which future directions or open questions excite you most?

Great question. Currently, there are a few different directions that are quite exciting. One direction is related to the recent developments that are happening in image generative models. We are developing diffusion based models which can generate very high quality images and can represent diverse concepts. However, one intriguing thing that people have found recently is that if you probe the visual representations that are learned by these models, they actually do not do very well on tasks like image classification. It’s quite interesting that, on one hand, these models are able to generate all these very nice looking images, but on the other hand, the information content in their visual representations is not good enough to do simple tasks like image classification. So I am interested in studying what are the systematic differences in the representations that are learned by image generative tasks versus image discriminative tasks? And how can we bridge this gap in the representations that are learned by two models. If we are able to do this, it will be quite impactful, because it will help us to create unified models that can do both understanding and generation without using different image encoders for each.

I’m also interested in embodied Al. In particular, how can we use the knowledge that exists in large models, like large language models or large vision language models (VLMs), for teaching low level control tasks to the embodied agents? So for example, if I want to teach my robot how to make an omelette, my LLM can tell me what the high-level steps are: break an egg, whisk it, put it on a pan, and things like that. But, if you talk to robotics people, they will say that that is not the difficult part. The difficult part is, how do you teach a robot how to break an egg? It has to hold the egg in a particular way and apply a particular amount of force. VLMs haven’t yet proven to be useful in this regard. But my hope is that they might still have some sort of knowledge stored inside them from all the internet data they have been trained on, such as how many Newtons of force needs to be applied to break an egg. The research question is how to extract that knowledge from VLMs and LLMs for these kinds of low level robot control tasks.

Were you always set on being a researcher?

I didn’t always have the clarity that I would be a researcher or a professor, and I would be leading a lab and guiding students. But one aspect of my personality – which is probably the reason why I am in this field – is just curiosity. I’ve always been the kind of student who would ask a lot of questions. And even after my undergrad, instead of taking a job right away, I wanted to go for a PhD merely because I wanted to understand things more. I felt like I hadn’t gotten an in-depth knowledge of any particular field. So it was just that curiosity of trying to understand things that drives me behind whatever I do. Even in my lab today, with my students, what drives me to do research is trying to understand how things work. And in our experiments, I encourage my students not just to build new models, but also to understand how the current models are working, so that you can get better insights into what to work on next. So it’s curiosity and trying to understand things that has always led me throughout my research career.

That’s a great driver. So my final question is – do you have any advice for any early career researchers in your field who might be setting out on a similar path to you?

I think my advice here is specifically targeted towards PhD students, Masters students, or even early career faculty. I’m sure a lot of them are going through this same questioning phase that I went through: how should I position my research? What is that I should work on? What problem should I work on? In the current landscape, where it can feel like a lot of the problems are already solved, it’s easy to ask yourself if there is a point to being in this research business.

The first piece of advice I would like to give is that what you work on specifically is not so important for helping you to achieve a great career ahead. What is more important is how you do the research. You could be working on a very hot shot problem, but if your execution is not well done or the findings are not insightful, then it is not going to be as impactful as if you were working on something which less people care about, but you contributed a new angle or new insights to that research. So I would advise students and early career researchers to think about doing things rigorously and well, and aim to contribute new insights and new angles. And I think that if you’re enjoying doing that and doing it well, you should be fine.

The second piece of advice is again, more for students. There isn’t a lot of emphasis on improving communication or presentation skills during PhD programs – most of the focus is on writing papers and contributing new research. But, as a researcher, having good presentation and communication skills matters quite a bit, and it matters more and more as you advance in your career. You have to write grant proposals, where you have to pitch your ideas in layman’s terms, and you have to convince someone who is not from your field to invest in your idea. You have to give presentations, talks, and again, convince a broader audience to take an interest, not just the audience who is working in your field. Investing time in improving your communication and presentation skills is very important. So are your written presentation skills – writing good papers that are easy to read and understand is very important.

About Aishwarya

|

Aishwarya Agrawal is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Computer Science and Operations Research at the University of Montreal. She is a Canada CIFAR AI Chair and a core academic member of Mila-Quebec Al Institute, and spends one day a week as a Research Scientist at Google DeepMind. Aishwarya’s research focus is on Multimodal research, specifically Vision-Language research. Aishwarya is a recipient of the 2025 Mark Everingham Prize, a ΑΙ Canada CIFAR AI Chair Award, a Young Alumni |

tags: AAAI, ACM SIGAI, AI Matters