ΑΙhub.org

Interview with Andrews Ata Kangah: Localising illegal mining sites using machine learning and geospatial data

Andrews Ata Kangah is a researcher working on democratizing AI and AI solutions for environmental problems. We spoke to him about his research, attending the AfriClimate AI workshop at the Deep Learning Indaba, and what inspired him to work in AI and on climate-related projects.

Could you start by telling us a bit about yourself – where are you working, and what’s your area of research?

My name is Andrews Ata Kangah. I am a researcher at Armtos, which is a non-profit. At Armtos, our current goal is to build a solution to solve the illegal mining problem that’s going on in Ghana. The mining is destroying the lands that are within mining areas.

You won an award at the Deep Learning Indaba workshop AfriClimate AI workshop. Could you tell us about the work that you won the award for?

In September, I travelled to Senegal to participate in the Deep Learning Indaba. I presented a paper on our model VitSegh24. I also presented at the AfriClimate AI workshop – this was a five-minute talk about how we can use AI to help stop illegal mining in Ghana. That was the work (“Combating Climate Change Due to Galamsey: Geospatial Image Data Classifier for Localising Illegal Mining Sites”) that won the award at the AfriClimate AI workshop.

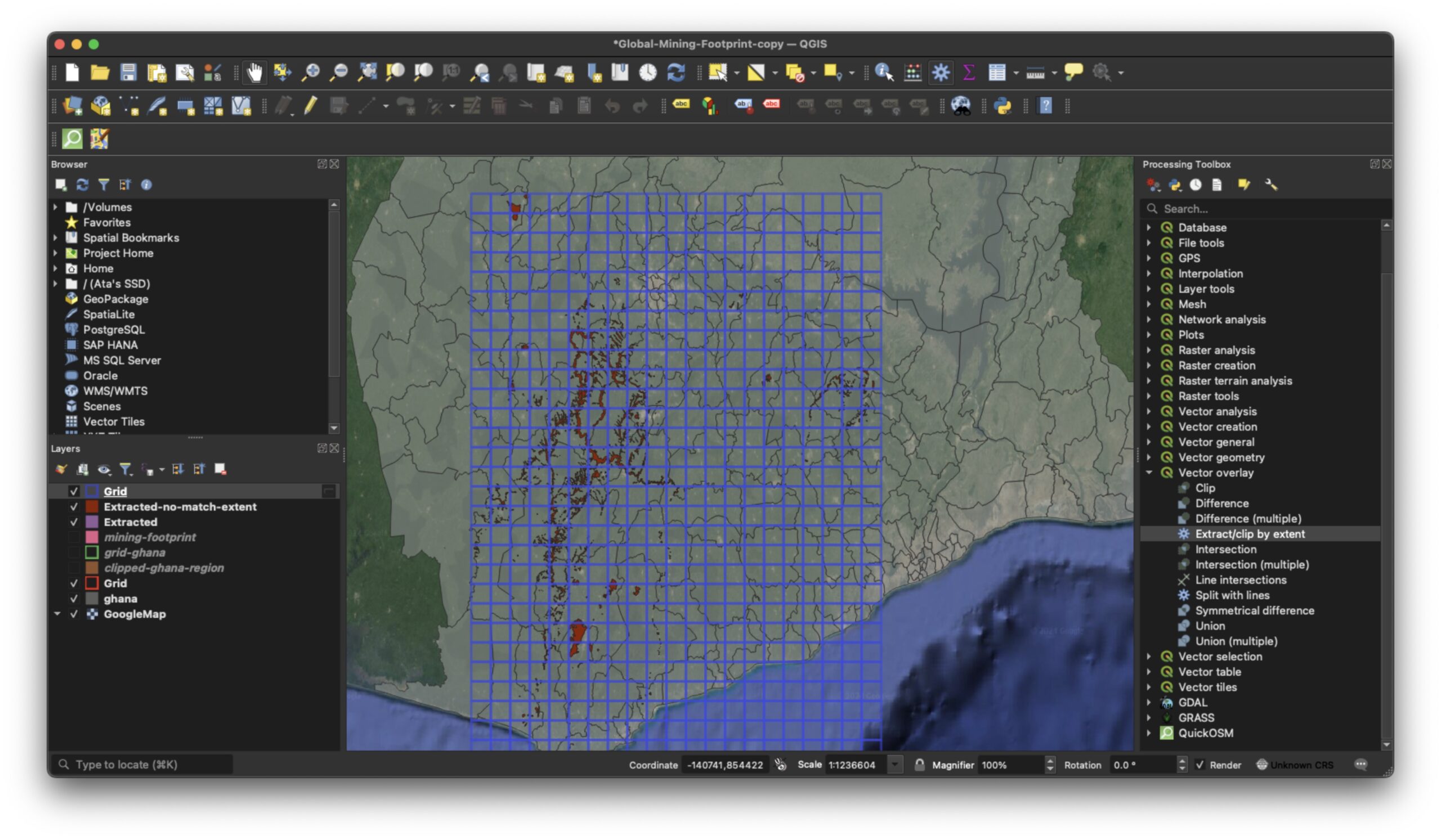

The project was related to the work I do at Armtos on illegal mining. At the moment, a lot of people in Ghana are angry at the government because this illegal mining has been going on for a long time, almost ten years now. The land and the rivers have been badly affected. Due to the mining, river bodies close to the mining sites can no longer serve as drinking water to nearby communities. I came up with the idea that we could use geospatial data and train a machine learning model that is able to segment out sections of the land where mining is going on. We can take the geospatial data and focus on the areas of concern, and the model segments out exactly where the mining is. We can stitch those images back together on a globe and see images of where the mining is actually taking place.

What the government used to do was find out where the illegal sites were by talking to people, then they’d go and try to seize the equipment. However, often, by the time they got to a site the miners had run away. It was taking them too long to find out where the new sites were. Our goal is to build a real-time system. If we can get images every few weeks or months, we can detect new mines, and the government can use this information to target the area. We now have a bird’s-eye view of new mines, and that is the first step in this project.

Did you meet anyone at the Deep Learning Indaba workshop who was working in a similar area that you could collaborate with?

Yes, I actually met a team of mining engineers! The company they work for is called Eramet. They came round to my stand at the conference and were really happy because they had been looking out for someone who was doing this kind of research. They were interested to hear what I had been doing.

I also met other researchers working on similar problems. For example, many people are working on different climate problems. During my literature review, I was able to get the contact details of some researchers in Canada who are working on a similar mining project. We are now collaborating with them to improve the performance of our model. But at Indaba actually, I was able to join the AfriClimate AI community which gave me access to a rich set of climate researchers like Santiago Hincapie and John Bagiliko who I discuss my ideas with and consider as friends.

What inspired you to work in the field of AI and on environmental problems?

I would say that there wasn’t one particular moment that made me want to work in AI. In fact, when I was studying, I was at the same time working with Darlington Akogo, CEO of Minohealth AI Labs, and he tried to put me on a course to learn machine learning, but I wasn’t really interested.

However, I have been building AI products for a while now and I’ve really begun to appreciate it. It’s great fun to work on AI, especially the current themes of my research. I think it was the constant involvement in the field that gave me the passion for it.

In terms of illegal mining, I’ve always been interested in the environment and how we can protect it. When I finished school I participated in some organised “clean-ups” in Ghana during my work at Turntabl Ghana Ltd. But way before that time, Google had a developer challenge programme where students could build a team, think of an idea, and work on it. It was about that same period that the concerns on the devastations of illegal mining to our natural environment started coming up. That was when I had the idea to build something like this, but, at that time, I didn’t know much about AI, geospatial data, or imaging.

It wasn’t until recently that I actually built my first model myself. I’ve now been involved in the AI field for a long time and have a lot more experience with AI models, having deployed a number of pretrained models myself. The motivation to finally start tackling the illegal mining issue in particular came from the Deep Learning Indaba AfriClimate AI workshop, and trying to meet the deadline for inclusion of my research in the Weakly Supervised Computer Vision workshop at the conference. At first I was not going to make any serious contribution, but then there were several calls for participation from the conference hosts so I decided to get involved. It was then that I remembered this idea about illegal mining and decided to go for it.

About Andrews

|

Andrews (Ata) Kangah is a researcher at Armtos, a non-profit focused on implementing solutions for the UN SDG goals and environmental protection and sustainability. His research focuses on applying machine learning, specifically Semantic Segmentation to identifying and localizing mining affected areas in Ghana. He is also a DevSecOps engineer at tech11 Gmbh. He also contributes his knowledge to the software direction at minohealth AI Labs. In the past, Ata contributed to The Startup and Better Programming on Medium as a content creator. He contributes his ideas and thoughts currently on Bluwr.com as THEJEDI. Ata was a mentor at the 2021 Google Africa Developers Scholarship Program as a cloud track instructor. In his early career, He worked as a Contingent Software Engineer at Morgan Stanley through Turntabl Ghana Ltd, where he contributed to the Central Tools team. |

tags: AfriClimate AI