ΑΙhub.org

Interview with Alice Xiang: Fair human-centric image dataset for ethical AI benchmarking

Alice Xiang

Earlier this month, Sony AI released a dataset that establishes a new benchmark for AI ethics in computer vision models. The research behind the dataset, named Fair Human-Centric Image Benchmark (FHIBE), has been published in Nature. FHIBE is the first publicly-available, globally-diverse, consent-based human image dataset (inclusive of over 10,000 human images) for evaluating bias across a wide variety of computer vision tasks. We sat down with project lead, Alice Xiang, Global Head of AI Governance at Sony Group and Lead Research Scientist for AI Ethics at Sony AI, to discuss the project and the broader implications of this research.

Could you start by introducing the project and taking us through some of the main contributions?

FHIBE was inspired by what we saw as a gap in the ecosystem. Even though algorithmic fairness has advanced significantly as a discipline in recent years, it’s very difficult for practitioners to actually assess their AI models for bias. When they do so, they often find themselves in a challenging situation of having to use public datasets that are not necessarily collected with appropriate consent and compensation for the data rights holders. This wasn’t something that we saw just at Sony, but at other companies as well.

I first became interested in this topic while working at the Partnership on AI. Across the industry, availability of appropriate data for bias evaluation was a significant issue. In academic papers, for example, researchers were always relying on the same, problematically-sourced datasets. It created a catch-22: if you wanted to make your model more ethical by trying to measure and mitigate its bias, you also had to rely on these very problematically-sourced datasets, ultimately undermining the ethical intentions initially set forth.

The goal of FHIBE was to move the space forward and provide something that AI developers could use to conduct bias diagnoses.

Initially, we thought that creating this dataset wouldn’t be that big of a deal – putting into practice the things that folks have recommended be done in ethical data collection. It turns out it’s very different to go from theory to actually doing this in practice. I think that’s one of the biggest contributions of FHIBE: that it’s coming from an ethics team putting into practice all of the recommendations that other ethicists, including us, have been advocating for and recommending.

As a result, FHIBE has several contributions. The first is raising the bar for ethical data collection in the human-centric computer vision realm, showing that AI developers can go far beyond the status quo when it comes to respecting data rights holders and being very careful about the types of content publicized in datasets. We hope this contributes to the broader conversation around the data being ingested by AI and what kind of rights people have around that.

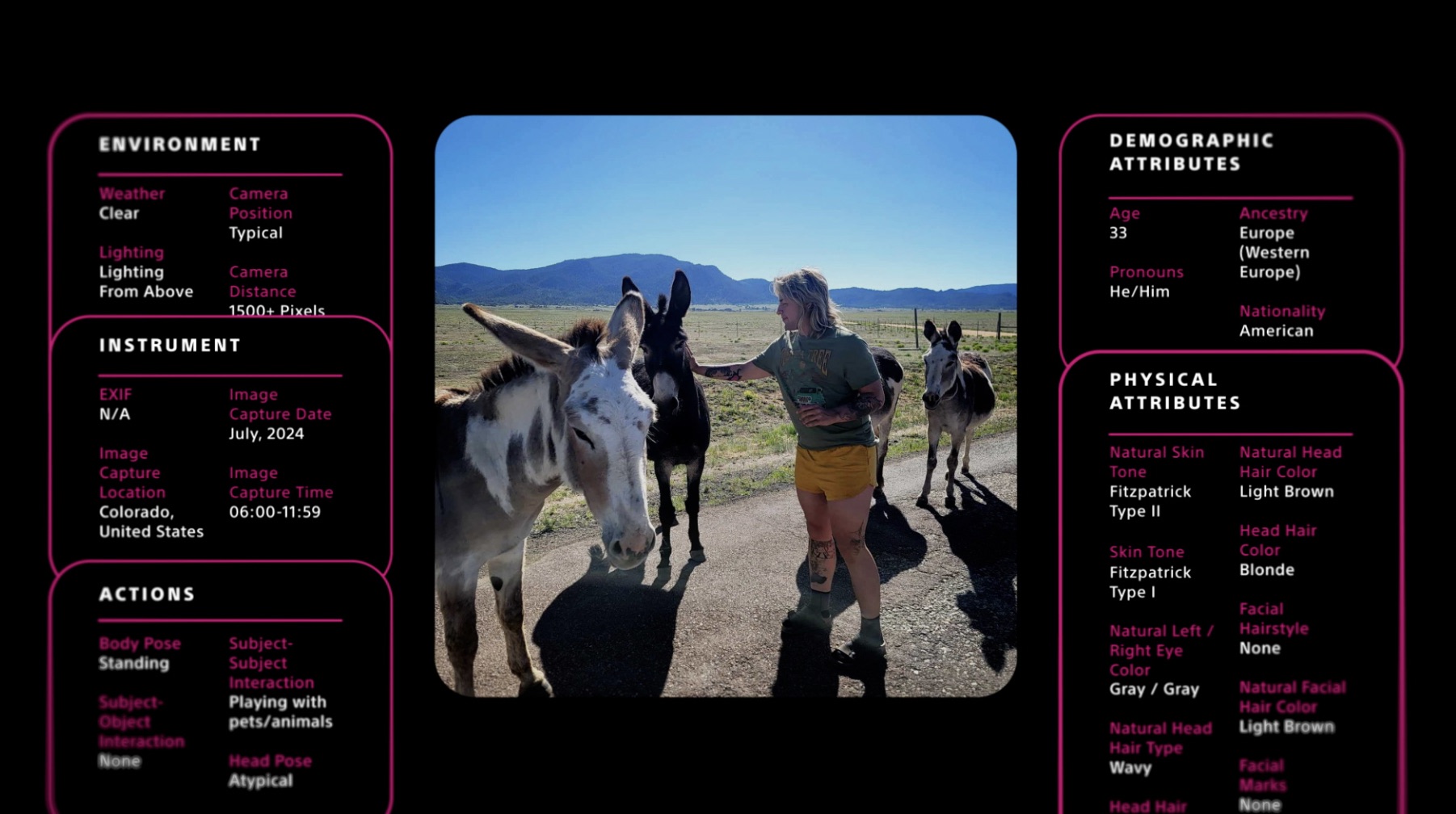

Another significant contribution is raising the standard around fairness benchmarking in this space. We have a much more diverse population compared to other consensually collected datasets, and we have extensive annotations that allow for much more granular bias diagnosis. It’s not just initial diagnosis across different demographic groups – you can go much deeper into attributes, like people’s hairstyles, eye colors, poses, or background context – to further examine where there might be problematic associations being learned by models that then contribute to the biased outcomes that we see.

Finally, there’s the practicality of the artifact itself. Folks can, in practice, use FHIBE to audit their own models for bias. In our paper, we found many biases that hadn’t previously been documented in literature by using FHIBE on a wide variety of different tasks and models. It’s a good starting point of showcasing some of the biases out there, and also providing a tool that researchers and developers can use for their own models to do this kind of exercise.

Image courtesy of Sony AI.

There are certainly a lot of impressive contributions in the work! It was three years in the making, is that right?

Yes, and if you include all of our ethical data work that has contributed to this, it’s probably more like five years that we’ve been researching this space. It’s been a huge undertaking from everyone who contributed, and also everyone on the vendor side, the data participants, and the quality assurance specialists. I think a lot of what makes this paper special is just how many pieces have to come together in order for it to achieve its goals.

I imagine it’s quite an interdisciplinary team, with different expertise across many different areas.

Yes, I think this project, in general, is an excellent example of the value of interdisciplinary research, because it involves so many different components. There’s various ethical and legal components in terms of how to design a consent process that is effective globally. There is a very complex regulatory landscape to navigate, and collecting data in a way that respects differing jurisdictions’ views of these data rights is quite complicated. And then there’s the technical components of the specifications for the dataset, the details of what kind of attributes we were collecting, and then actually trying to verify the quality of the data. There’s also the analysis that goes into the different biases, as well as trying to benchmark those. The project had many different layers, and I think it could have been much more difficult if we had only been taking one perspective on the issue.

What would you say were some of the main challenges?

There were many challenges throughout the course of the project. Any time you’re trying to do something ethical in practice, you’ll encounter many challenges for a few reasons. One is that, when you’re talking abstractly about AI ethics, it’s very easy to produce a long list of desiderata that all seem reasonable and valuable. But in practice, these are often in tension with each other, and there might not be a clear path to the right answer. You are often doing a complex balancing exercise to try to find something in between that optimizes as much as possible for multiple desiderata, but still is practically feasible. To make that more concrete, for instance, there were some inherent tensions between fairness and utility and privacy. In order for this to be as useful as possible for the community, it needed to be public, and then we also wanted to be as globally diverse and representative as possible. Then you also have to think about it from a privacy perspective. You’re putting people’s data publicly, so you want to be quite careful about what data will be released and very mindful of how it’s communicated to participants. We did draw lines on a few things – such as not collecting data from children because even though that would have been beneficial from a utility and diversity perspective, from a privacy and rights perspective, it can be very complicated. There are many of these sorts of balancing acts that we had to consider when we were designing the project.

We also had to think carefully about the specific attributes we collected. For example, we collected gender pronouns, which hasn’t really been a norm in computer vision in the past. Gender identities or sex weren’t collected because they can be quite sensitive in terms of what kind of information participants might disclose and also how you characterize them. Gender pronouns are something that folks more typically disclose publicly and are less directly revealing about their core identity, history or biology. Of course, if you don’t have any of these sensitive attributes in your dataset, it’s not going to be useful as a fairness benchmark, but this is a very sensitive space where you have to be extremely mindful and careful about what you’re disclosing.

There were many practical implementation challenges as well. We were working with a variety of data vendors, and our project, in terms of what we were asking for, was much more complicated than anything that they had dealt with previously. The project ended up being a lot more complex, time-consuming, and difficult than we expected because we also had to spend a lot of time building up our infrastructure on the quality assurance side to really ensure that we were able to get data up to our specifications.

Image courtesy of Sony AI.

Has the dataset already been integrated in some of the other projects at Sony AI?

We released FHIBE internally within Sony before the external release, and we have already seen a number of teams using it to check for bias in their models, which has been quite gratifying.

I also lead our AI Governance Office, which is the entity responsible for AI governance compliance across Sony Group. We receive a lot of these fairness assessments as part of the broader AI ethics assessments we do with business and R&D teams, and it’s been great to see FHIBE popping up there. Since its public release, we’ve also seen many downloads from a wide variety of institutions. We’re hopeful folks will evaluate their models and use FHIBE as the first step for addressing biases in them.

This dataset is intended for benchmarking, right? It’s not a training dataset.

Yes – and this is an important distinction since we are releasing a lot of annotations, including about people’s demographics. We didn’t want this data to be used for training race or gender classifiers, and we prohibit such uses in our Terms of Use. It was important that these sensitive attributes be used specifically for bias evaluation and mitigation and not for other purposes.

Do you think that FHIBE will prompt other organizations or companies to do something similar, and what are your hopes for future research and development in this space?

FHIBE was a very difficult project. I spent a lot of time talking to people at other companies and institutions to see if they’d done anything in this realm, because the idea was for a public benchmark that everyone could use. In those conversations, it became clear that this was a problem everyone was grappling with, but no one had yet built a solution. One of our hopes with FHIBE is that it’s like a proof of concept, showing that there doesn’t have to be this dichotomy where you can either have data for AI and it’s unethically sourced, or you don’t have AI.

We are also hopeful that FHIBE provides a blueprint and starting point where it’s much easier for others to copy, paste, and scale up compared to doing it all the first time. We hope this really inspires and galvanizes more folks across the industry since it’s much more of a repeatable project now. That doesn’t mean that FHIBE is the end-all, be-all. Ideally, this inspires folks to do more R&D on the scalability question. I think generally in AI there’s been the sentiment that if you want to train state-of-the-art models, you need as much data as possible, and in order to get as much data as possible, it has to be as close to the whole internet as you can get. Already we’re seeing pushback in terms of questions about whether AI can continue to progress just by that data scaling logic. The hope is that, in general, people might be thinking a little bit more about how to train models on smaller datasets. Simultaneously, with the work that we have with FHIBE, hopefully people are thinking about how to collect said datasets in more ethical ways. Maybe we can meet in the middle in terms of what is feasible to collect ethically versus what is necessary for training state-of-the-art models.

Additionally, we hope that researchers see this and feel that there is a lot of value in investing in data collection, even for smaller datasets. Oftentimes data collection is perceived as a thankless task, and some researchers might not view it as being as meaningful of a scientific contribution as making some algorithmic advances. When we talk about trying to make AI more ethical, however, the fundamental challenge is this garbage in, garbage out problem. Yes, there are things you can do later in the development process to address some of the issues of bias, but to actually holistically develop AI more ethically, you really have to start at the data layer. For some of the issues that FHIBE grapples with, like consent and compensation, there’s no patching you can do on the tail end in order to address those fundamental problems with the training side. Our big goal with FHIBE is to increase awareness of data ethics issues and inspire people to do better when it comes to data collection.

About Alice

|

Alice Xiang is the Global Head of AI Governance at Sony. As the Vice President responsible for AI ethics and governance across Sony Group, she leads the team that guides the establishment of AI governance policies and governance frameworks across Sony’s business units. In addition, as the Lead Research Scientist for AI ethics at Sony AI, Alice leads a lab of AI researchers working on cutting-edge sociotechnical research to enable the development of more responsible AI solutions. Alice holds a Juris Doctor from Yale Law School, a Master’s in Development Economics from Oxford, a Master’s in Statistics from Harvard, and a Bachelor’s in Economics from Harvard. |

You can watch Sony AI’s film about the FHIBE project here.