ΑΙhub.org

Adapting on the fly to test time distribution shift

By Marvin Zhang

Imagine that you are building the next generation machine learning model for handwriting transcription. Based on previous iterations of your product, you have identified a key challenge for this rollout: after deployment, new end users often have different and unseen handwriting styles, leading to distribution shift. One solution for this challenge is to learn an adaptive model that can specialize and adjust to each user’s handwriting style over time. This solution seems promising, but it must be balanced against concerns about ease of use: requiring users to provide feedback to the model may be cumbersome and hinder adoption. Is it possible instead to learn a model that can adapt to new users without labels?

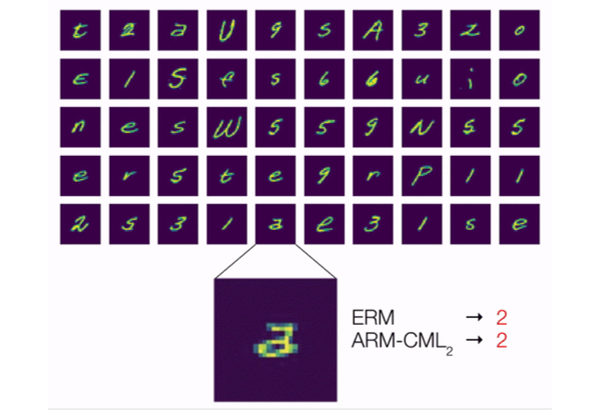

In many scenarios, including this example, the answer is “yes”. Consider the ambiguous example shown enlarged in the figure below. Is this character a “2” with a loop or a double-storey “a”? For a non adaptive model that pays attention to the biases in the training data, the reasonable prediction would be “2”. However, even without labels, we can extract useful information from the user’s other examples: an adaptive model, for example, can observe that this user has written “2”s without loops and conclude that this character is thus more likely to be “a”.

Handling the distribution shift that arises from deploying a model to new users is an important motivating example for unlabeled adaptation. But, this is far from the only example. In an ever-changing world, autonomous cars need to adapt to new weather conditions and locations, image classifiers need to adapt to new cameras with different intrinsics, and recommender systems need to adapt to users’ evolving preferences. Humans have demonstrated the ability to adapt without labels by inferring information from the distribution of test examples. Can we develop methods that can allow machine learning models to do the same?

This question has enjoyed growing attention from researchers, with a number of recent works proposing methods for unlabeled test time adaptation. In this post, I will survey these works as well as other prominent frameworks for handling distribution shift. With this broader context in mind, I will then discuss our recent work (see the paper here and the code here), in which we propose a problem formulation that we term adaptive risk minimization, or ARM.

Diving into Distribution Shift

The vast majority of work in machine learning follows the canonical framework of empirical risk minimization, or ERM. ERM methods assume that there is no distribution shift, so the test distribution exactly matches the training distribution. This assumption simplifies the development and analysis of powerful machine learning methods but, as discussed above, is routinely violated in real-world applications. To move beyond ERM and learn models that generalize in the face of distribution shift, we must introduce additional assumptions. However, we must carefully choose these assumptions such that they are still realistic and broadly applicable.

How do we maintain realism and applicability? One answer is to model the assumptions on the conditions that machine learning systems face in the real world. For example, in the ERM setting, models are evaluated on each test point one at a time, but in the real world, these test points are often available sequentially or in batches. For handwriting transcription, for example, we can imagine collecting entire sentences and paragraphs from new users. If there is distribution shift, observing multiple test points can be useful either to infer the test distribution or otherwise adapt the model to this new distribution, even in the absence of labels.

Many recent methods that use this assumption can be classified as test time adaptation, including batch normalization, label shift estimation, rotation prediction, entropy minimization, and more. Oftentimes, these methods build in strong inductive biases that enable useful adaptation; for example, rotation prediction is well aligned with many image classification tasks. But these methods generally either propose heuristic training procedures or do not consider the training procedure at all, relying instead on pretrained models.1 This begs the question: can test time adaptation be further enhanced by improved training, such that the model can make better use of the adaptation procedure?

We can gain insight into this question by investigating other prominent frameworks for handling distribution shift and, in particular, the assumptions these frameworks make. In real-world applications, the training data generally does not consist only of input label pairs; instead, there are additional meta-data associated with each example, such as time and location, or the particular user in the handwriting example. These meta-data can be used to organize the training data into groups,2 and a common assumption in a number of frameworks is that the test time distribution shifts represent either new group distributions or new groups altogether. This assumption still allows for a wide range of realistic distribution shifts and has driven the development of numerous practical methods.

For example, domain adaptation methods typically assume access to two training groups: source and target data, with the latter being drawn from the test distribution. Thus, these methods augment training to focus on the target distribution, such as through importance weighting or learning invariant representations. Methods for group distributionally robust optimization and domain generalization do not directly assume access to data from the test distribution, but instead use data drawn from multiple training groups in order to learn a model that generalizes at test time to new groups (or new group distributions). So, these prior works have largely focused on the training procedure and generally do not adapt at test time (despite the name “domain adaptation”).

Combining Training and Test Assumptions

Prior frameworks for distribution shift have assumed either training groups or test batches, but we are not aware of any prior work that uses both assumptions. In our work, we demonstrate that it is precisely this conjunction that allows us to learn to adapt to test time distribution shift, by simulating both the shift and the adaptation procedure at training time. In this way, our framework can be understood as a meta-learning framework, and we refer interested readers to this blog post for a detailed overview of meta-learning.

Adaptive Risk Minimization

Our work proposes adaptive risk minimization, or ARM, which is a problem setting and objective that makes use of both groups at training time and batches at test time. This synthesis provides a general and principled answer, through the lens of meta-learning, to the question of how to train for test time adaptation. In particular, we meta-train the model using simulated distribution shifts, which is enabled by the training groups, such that it exhibits strong post-adaptation performance on each shift. The model therefore directly learns how to best leverage the adaptation procedure, which it then executes in the exact same way at test time. If we can identify which test distribution shifts are likely, such as seeing data from new end users, then we can better construct simulated training shifts, such as sampling data from only one particular training user.

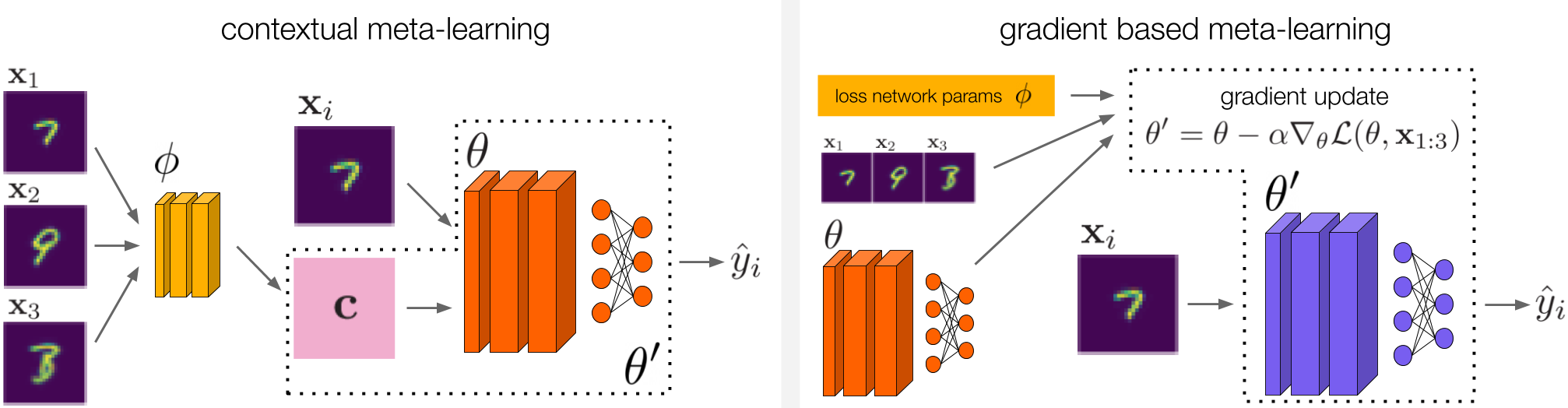

The training procedure for optimizing the ARM objective is illustrated in the graphic above. From the training data, we sample different batches that simulate different group distribution shifts. An adaptation model then has the opportunity to adapt the model parameters using the unlabeled examples. This allows us to meta-train the model for post-adaptation performance by directly performing gradient updates on both the model and the adaptation model.

We draw inspiration from contextual meta-learning (left) and gradient based meta-learning (right) in order to devise methods for ARM. For contextual meta-learning, we investigate two different methods that fall under this category. These methods are described in detail in our paper.

The connection to meta-learning is one key advantage of the ARM framework, as we are not starting from scratch when devising methods for solving ARM. In our work in particular, we draw inspiration from both contextual meta-learning and gradient based meta-learning to develop three methods for solving ARM, which we name ARM-CML, ARM-BN, and ARM-LL. We omit the details of these methods here, but they are illustrated in the figure above and described in full in our paper.

The diversity of methods that we construct demonstrate the versatility and generality of the ARM problem formulation. But do we actually observe empirical gains using these methods? We investigate this question next.

Experiments

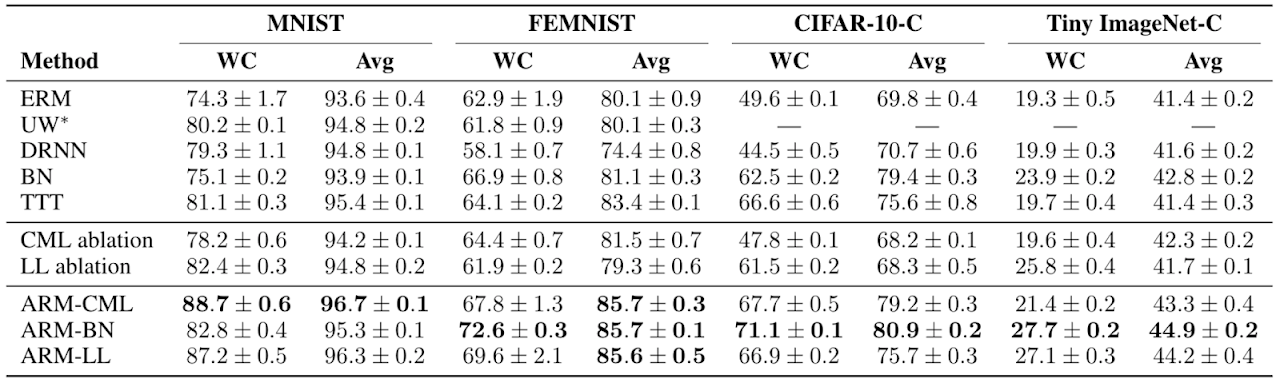

In our experiments, we first conducted a thorough study of the proposed ARM methods compared to various baselines, prior methods, and ablations, on four different image classification benchmarks exhibiting group distribution shift. Our paper provides full details on the benchmarks and comparisons.

We found that ARM methods empirically resulted in both better worst case (WC) and average (Avg) performance across groups compared to prior methods, indicating both better robustness and performance from the final trained models.

In our main study, we found that ARM methods do better across the board both in terms of worst case and average test performance across groups, compared to a number of prior methods along with other baselines and ablations. The simplest method of ARM-BN, which can be implemented in just a few lines of additional code, often performed the best. This empirically shows the benefits of meta-learning, in that the model can be meta-trained to take greater advantage of the adaptation procedure.

We also conducted some qualitative analyses, in which we investigated a test situation similar to the motivating example described at the beginning with a user that wrote double-storey a’s. We empirically found that models trained with ARM methods did in fact successfully adapt and predict “a” in this situation, when given enough examples of the user’s handwriting that included other “a”s and “2”s. Thus, this confirms our original hypothesis that training adaptive models is an effective way to deal with distribution shift.

We believe that the motivating example from the beginning as well as the empirical results in our paper convincingly argue for further study into general techniques for adaptive models. We have presented a general scheme for meta-training these models to better harness their adaptation capabilities, but a number of open questions remain, such as devising better adaptation procedures themselves. This broad research direction will be crucial for machine learning models to truly realize their potential in complex, real-world environments.

Thanks to Chelsea Finn and Sergey Levine for providing valuable feedback on this post.

Part of this post is based on the following paper:

- Marvin Zhang*, Henrik Marklund*, Nikita Dhawan*, Abhishek Gupta, Sergey Levine, Chelsea Finn.

Adaptive Risk Minimization: A Meta-Learning Approach for Tackling Group Shift.

Project webpage

Open source code

This article was initially published on the BAIR blog, and appears here with the authors’ permission.