ΑΙhub.org

EvolveGraph: dynamic neural relational reasoning for interacting systems

By Jiachen Li

Multi-agent interacting systems are prevalent in the world, from purely physical systems to complicated social dynamic systems. The interactions between entities / components can give rise to very complex behavior patterns at the level of both individuals and the multi-agent system as a whole. Since usually only the trajectories of individual entities are observed without any knowledge of the underlying interaction patterns, and there are usually multiple possible modalities for each agent with uncertainty, it is challenging to model their dynamics and forecast their future behaviors.

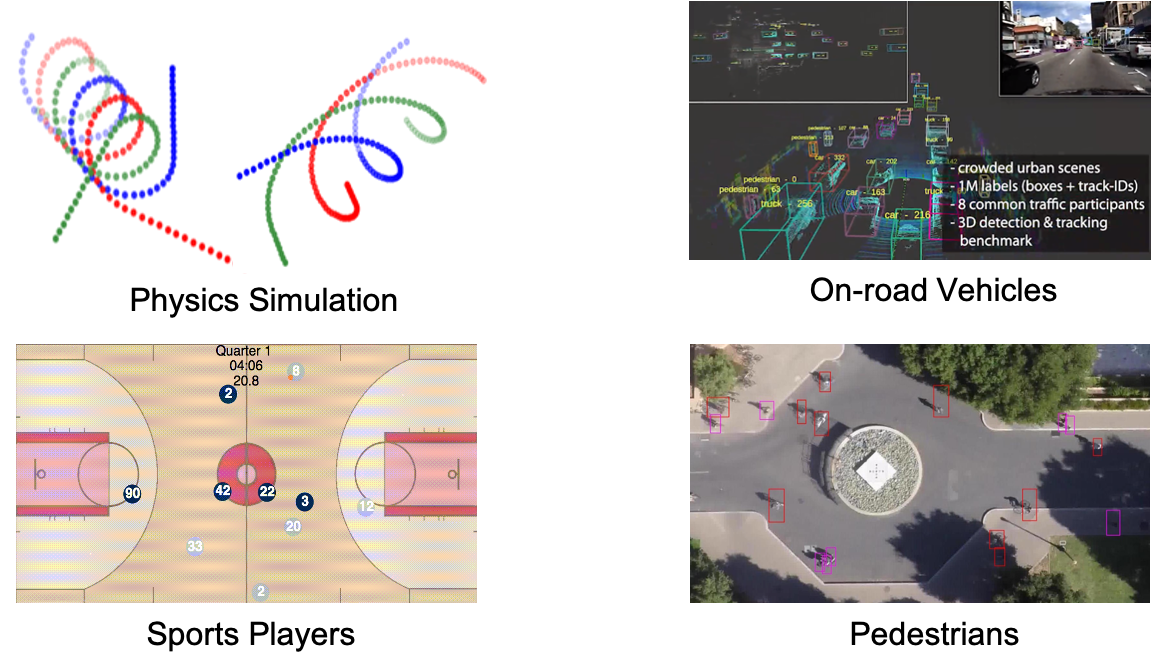

Figure 1. Typical multi-agent interacting systems.

In many real-world applications (e.g. autonomous vehicles, mobile robots), an effective understanding of the situation and accurate trajectory prediction of interactive agents play a significant role in downstream tasks, such as decision making and planning. We introduce a generic trajectory forecasting framework (named EvolveGraph) with explicit relational structure recognition and prediction via latent interaction graphs among multiple heterogeneous, interactive agents. Considering the uncertainty of future behaviors, the model is designed to provide multi-modal prediction hypotheses. Since the underlying interactions may evolve even with abrupt changes over time, and different modalities of evolution may lead to different outcomes, we address the necessity of dynamic relational reasoning and adaptively evolving the interaction graphs.

Challenges of Multi-Agent Behavior Prediction

Figure 2. An illustration of a typical urban intersection scenario.

We use an urban intersection scenario with multiple interacting traffic participants as an illustrative example to elaborate on the major challenges of the multi-agent behavior prediction task.

-

First, there may be heterogeneous agents that have distinct behavior patterns, thus using a homogeneous dynamics / behavior model may not be sufficient. For example, there are different constraints and traffic rules for vehicles and pedestrians. More specifically, vehicle trajectories are strictly constrained by road geometry and their own kinematic models; while pedestrian behaviors are much more flexible.

-

Second, there may be various types of interaction patterns in a multi-agent system. For example, the inter-vehicle interaction, inter-pedestrian interaction, and vehicle-pedestrian interaction in the same scenario present very different patterns.

-

Third, the interaction patterns may evolve over time as the situation changes. For example, when a vehicle is going straight, it only needs to consider the behavior of the leading vehicle; however, when the vehicle plans to change lanes, the vehicles in the target lane are also necessary to be taken into account, which leads to a change in the interaction patterns.

-

Last but not least, there may be uncertainties and multi-modalities in the future behaviors of each agent, which leads to various outcomes. For example, in an intersection, the vehicle may either go straight or take a turn.

In this work, we took a step forward to handle these challenges and provided a generic framework for trajectory prediction with dynamic relational reasoning for multi-agent systems. More specifically, we address the problem of

- extracting the underlying interaction patterns with a latent graph structure, which is able to handle different types of agents in a unified way,

- capturing the dynamics of interaction graph evolution for dynamic relational reasoning,

- predicting future trajectories (state sequences) based on the historical observations and the latent interaction graph, and

- capturing the uncertainty and multi-modality of future system behaviors.

Relational Reasoning with Graph Representation

Observation Graph and Interaction Graph

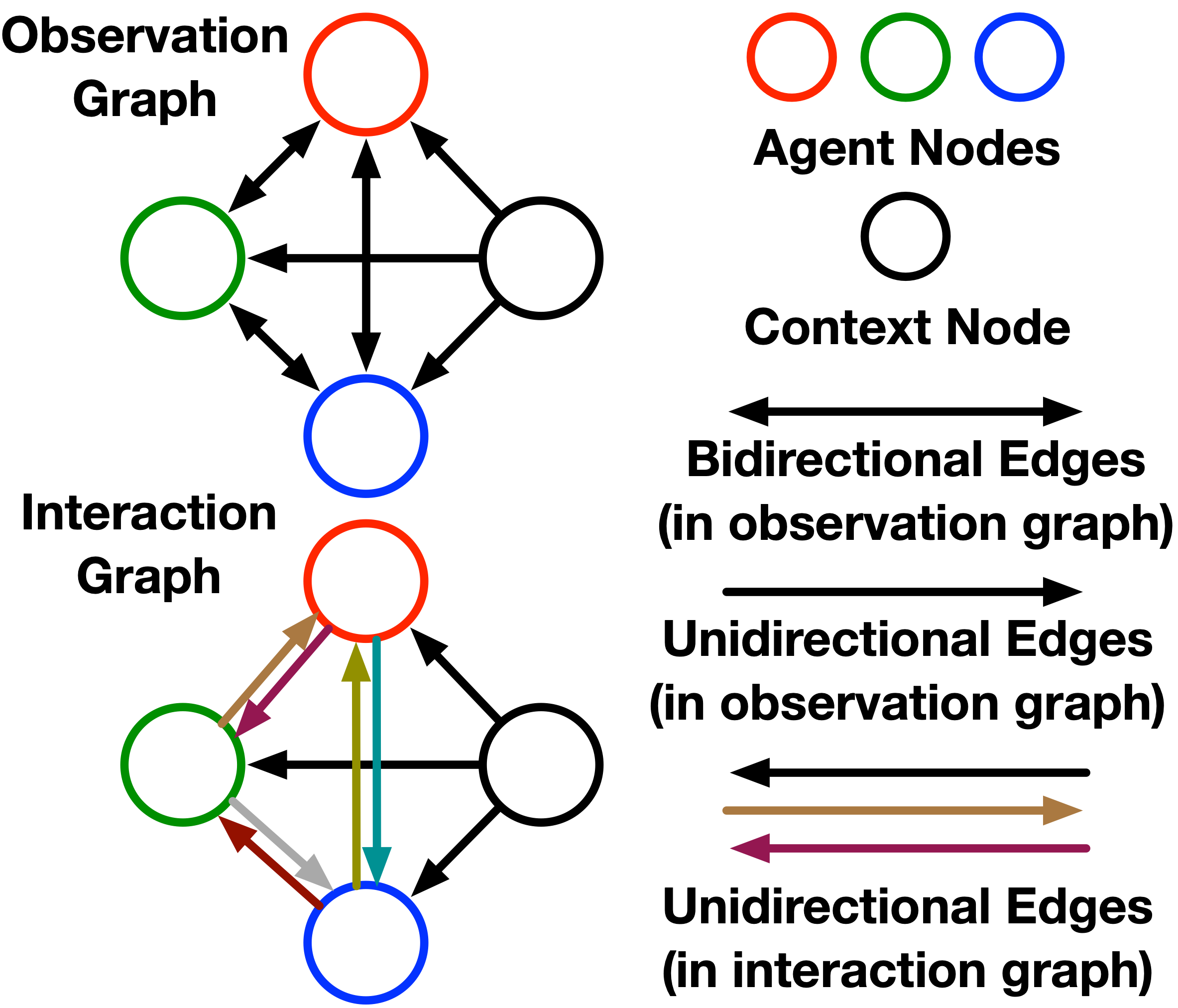

Figure 3. An illustration of the observation graph and interaction graph.

The multi-agent interacting system is naturally represented by a graph, where agents are considered as nodes and their relations are considered as edges. We have two types of graphs for different purposes, which are introduced below:

- Observation Graph: The observation graph aims to extract feature embeddings from raw observations, which consists of N agent nodes and one context node. Agent nodes are bidirectionally connected to each other, and the context node only has outgoing edges to each agent node. Each agent node has two types of attributes: self-attribute and social-attribute. The former only contains the node’s own state information, while the latter only contains other nodes’ state information.

- Interaction Graph: We use different edge types to represent distinct interaction patterns. No edge between a pair of nodes means that the two nodes have no relation. The interaction graph represents interaction patterns with a distribution of edge types for each edge, which is built on top of the observation graph.

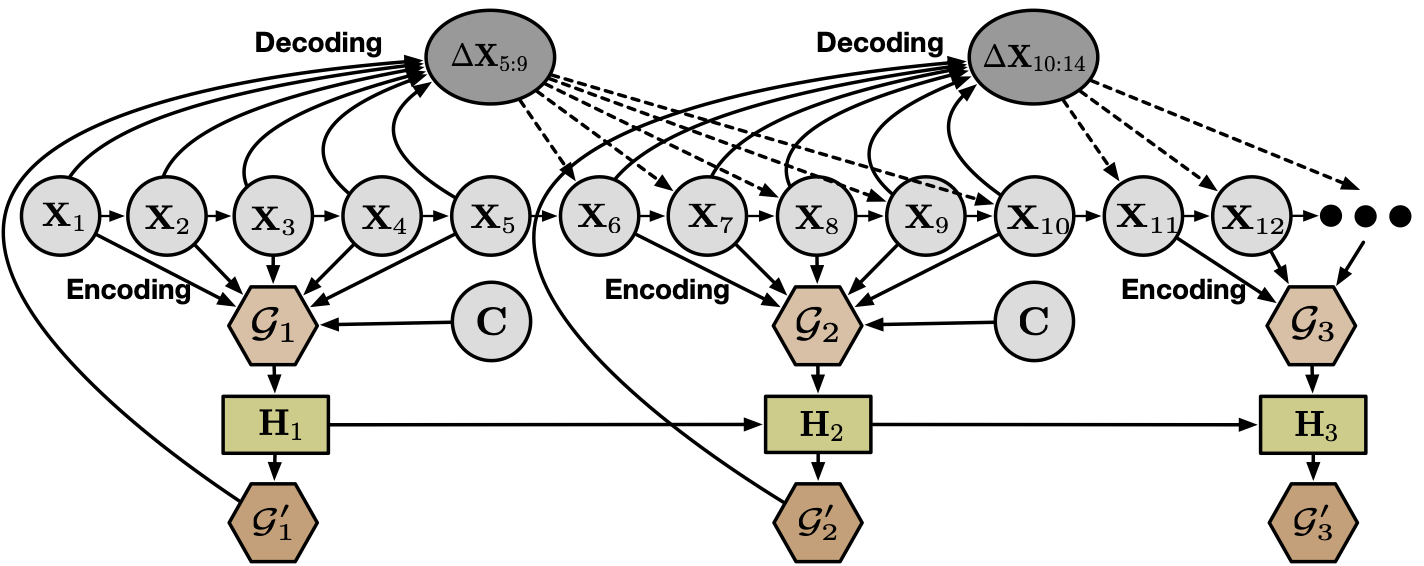

Figure 4. A high-level graphical illustration of EvolveGraph.

Dynamic Interaction Graph Learning

In many situations, the interaction patterns recognized from the past time steps are likely not static in the future. Moreover, many interaction systems have multi-modal properties in nature. Different modalities afterwards are likely to result in different interaction patterns and outcomes. Therefore, we designed a dynamic evolving process of the interaction patterns.

As illustrated in Figure 4, the encoding process is repeated every τ (re-encoding gap) time steps to obtain the latent interaction graph based on the latest observation graph. A recurrent unit (GRU) is utilized to maintain and propagate the history information, as well as to adjust the prior interaction graphs. More details can be found in our paper.

Uncertainty and Multi-Modality

Here we emphasize the efforts to encourage diverse and multi-modal trajectory prediction and generation. In our framework, the uncertainty and multi-modality mainly come from three aspects:

- First, in the decoding process, we output Gaussian mixture distributions indicating that there are several possible modalities at the next step. We only sample a single Gaussian component at each step based on the component weights which indicate the probability of each modality.

- Second, different sampled trajectories will lead to different interaction graph evolution. Evolution of interaction graphs contributes to the multi-modality of future behaviors, since different underlying relational structures enforce different regulations on the system behavior and lead to various outcomes.

- Third, directly training such a model, however, tends to collapse to a single mode. Therefore, we employ an effective mechanism to mitigate the mode collapse issue and encourage multi-modality. During training, we run the decoding process d times, which generates trajectories for each agent under specific scenarios. We only choose the prediction hypothesis with the minimal loss for backpropagation, which is the most likely to be in the same mode as the ground truth. The other prediction hypotheses may have much higher loss, but it doesn’t necessarily imply that they are implausible. They may represent other potential reasonable modalities.

Experiments

We highlight the results of two case studies on a synthetic physics system and an urban driving scenario. More experimental details and case studies on pedestrians and sports players can be found in our paper.

Case Study 1: Particle Physics System

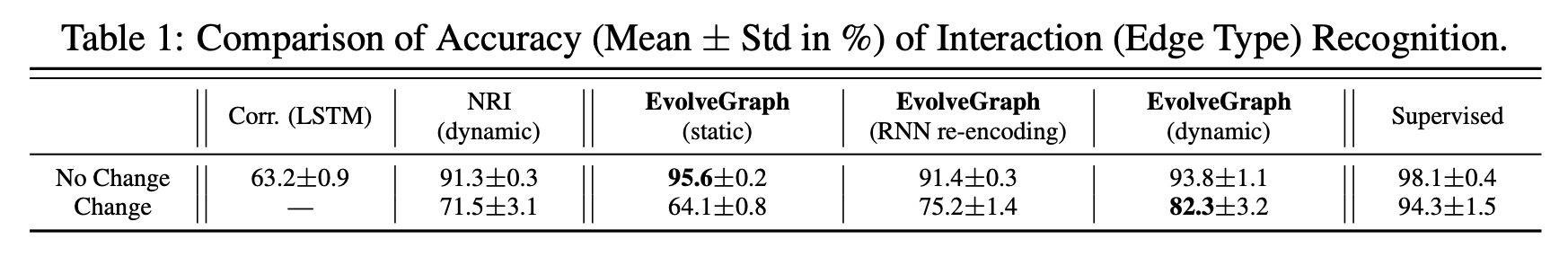

We experimented with a simulated particle system with a change of relations. Multiple particles are initially linked and move together. The links disappear as long as a certain criterion on the particle state is satisfied and the particles move independently thereafter. The model is expected to learn the criterion by itself and perform both edge type prediction and trajectory prediction. Since the system is deterministic in nature, we do not consider multi-modality in this task.

We predicted the particle states at the future 50 time steps based on the observations of 20 time steps. We set two edge types in this task, which correspond to “with link” and “without link”. The results of edge type prediction are summarized in Table 1, which are averaged over 3 independent runs. “No Change” means the underlying interaction structure keeps the same in the whole horizon, while “Change” means the change of interaction patterns happens at some time. It shows that the supervised learning baseline, which directly trains the encoding functions with ground truth labels, performs the best in both setups and serves as a “gold standard”. Under the “No Change” setup, NRI (dynamic) is comparable to EvolveGraph (RNN re-encoding), while EvolveGraph (static) achieves the best performance. The reason is that the dynamic evolution of the interaction graph leads to higher flexibility but may result in larger uncertainty, which affects edge prediction in the systems with static relational structures. Under the “Change” setup, NRI (dynamic) re-evaluates the latent graph at every time step during the testing phase, but it is hard to capture the dependency between consecutive graphs, and the encoding functions may not be flexible enough to capture the evolution. EvolveGraph (RNN re-encoding) performs better since it considers the dependency of consecutive steps during the training phase, but it still captures the evolution only at the feature level instead of the graph level. EvolveGraph (dynamic) achieves significantly higher accuracy than the other baselines (except Supervised), due to the explicit evolution of interaction graphs.

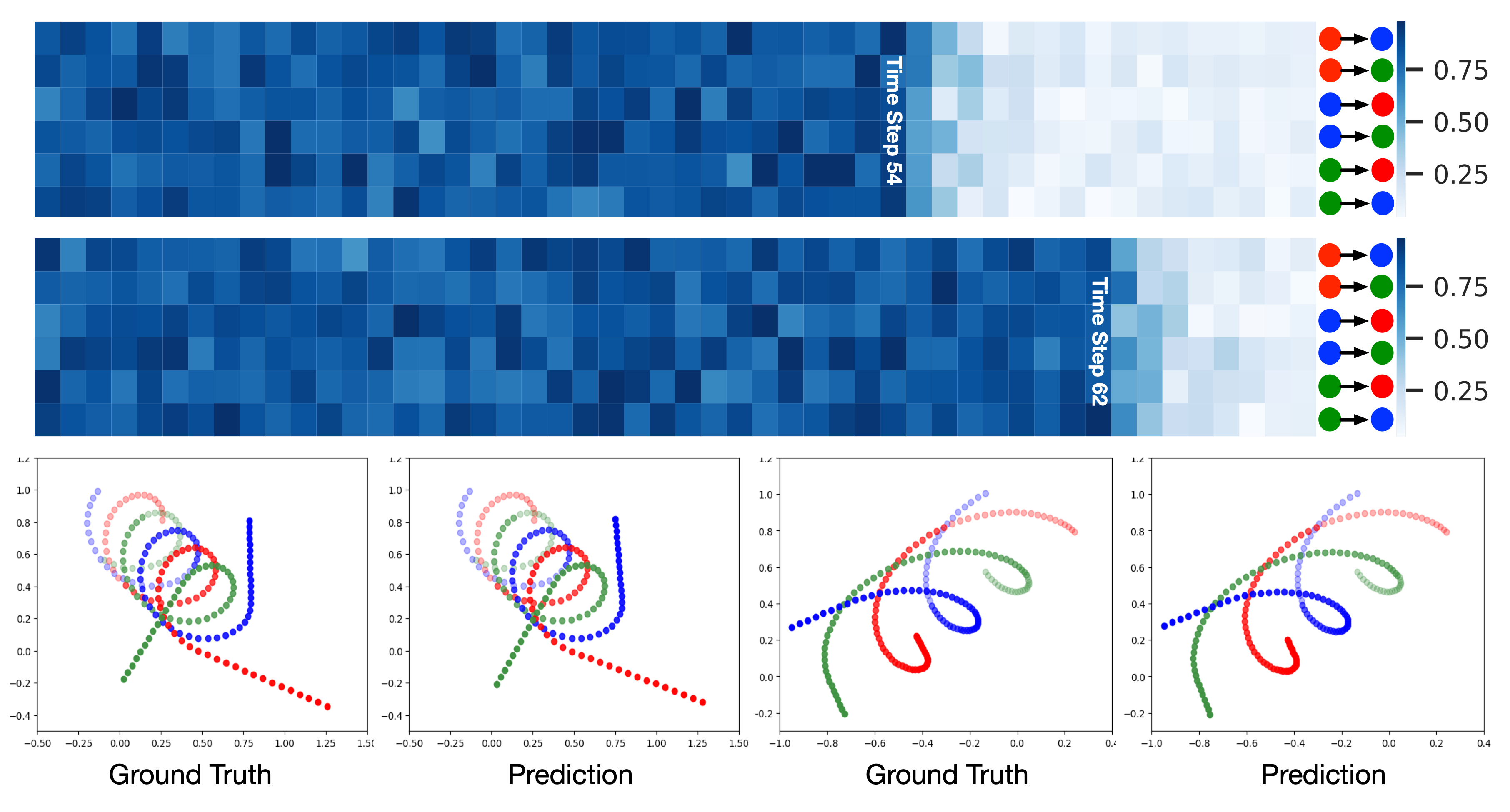

Figure 5. Visualization of latent interaction graph evolution and particle trajectories. (a) The top two figures show the probability of the first edge type (“with link”) at each time step. Each row corresponds to a certain edge (shown in the right). The actual times of graph evolution are 54 and 62, respectively. The model is able to capture the underlying criterion of relation change and further predict the change of edge types with nearly no delay. (b) The figures in the last row show trajectory prediction results, where semi-transparent dots are historical observations.

Case Study 2: Traffic Scenarios

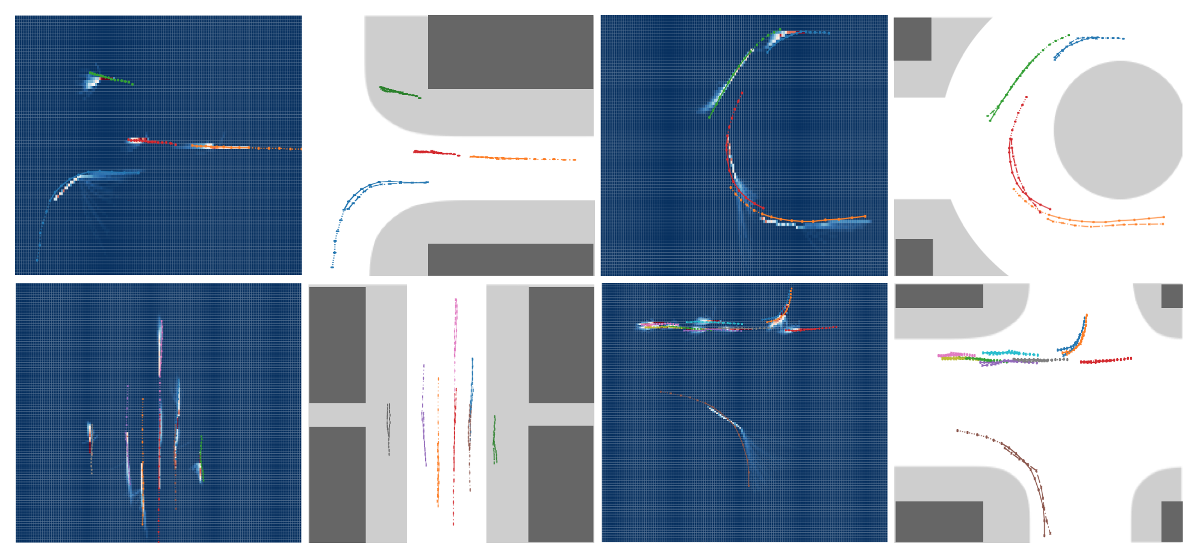

Figure 6. Visualization of testing cases in traffic scenarios. Dashed lines are historical trajectories, solid lines are ground truth, and dash-dotted lines are prediction hypotheses. White areas represent drivable areas and gray areas represent sidewalks. We plotted the prediction hypothesis with the minimal average prediction error, and the heatmap to represent the distributions.

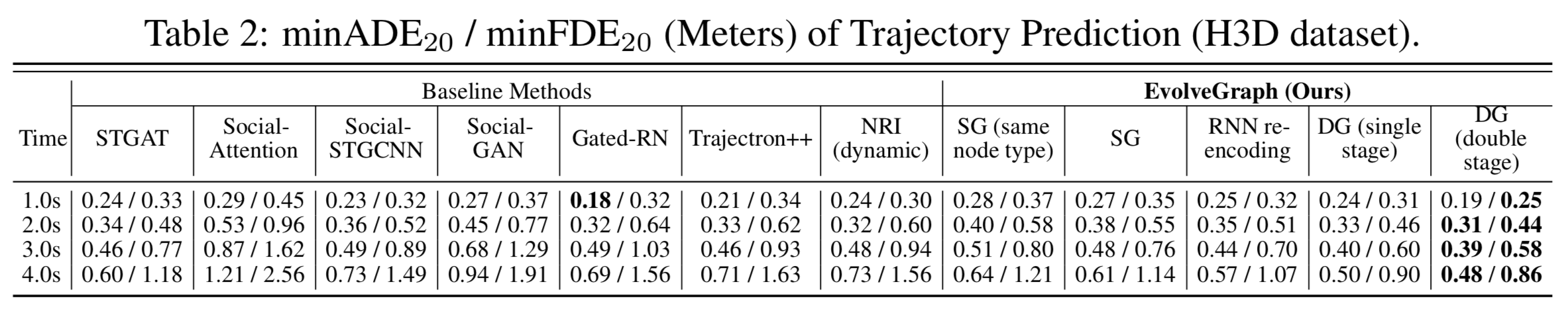

We predicted the future 10 time steps (4.0s) based on the historical 5 time steps (2.0s). The comparison of quantitative results is shown in Table 2, where the unit of reported ![]() and

and ![]() is meters in the world coordinates. All the baseline methods consider the relations and interactions among agents. The Social-Attention employs spatial attention mechanisms, while the Social-GAN demonstrates a deep generative model which learns the data distribution to generate human-like trajectories. The Gated-RN and Trajectron++ both leverage spatio-temporal information to involve relational reasoning, which leads to smaller prediction error. The NRI infers a latent interaction graph and learns the dynamics of agents, which achieves similar performance to Trajectron++. The STGAT and Social-STGCNN further take advantage of the graph neural network to extract relational features in the multi-agent setting. Our proposed method achieves the best performance, which implies the advantages of explicit interaction modeling via evolving interaction graphs. The 4.0s

is meters in the world coordinates. All the baseline methods consider the relations and interactions among agents. The Social-Attention employs spatial attention mechanisms, while the Social-GAN demonstrates a deep generative model which learns the data distribution to generate human-like trajectories. The Gated-RN and Trajectron++ both leverage spatio-temporal information to involve relational reasoning, which leads to smaller prediction error. The NRI infers a latent interaction graph and learns the dynamics of agents, which achieves similar performance to Trajectron++. The STGAT and Social-STGCNN further take advantage of the graph neural network to extract relational features in the multi-agent setting. Our proposed method achieves the best performance, which implies the advantages of explicit interaction modeling via evolving interaction graphs. The 4.0s ![]() /

/ ![]() are significantly reduced by 20.0% / 27.1% compared to the best baseline approach (STGAT).

are significantly reduced by 20.0% / 27.1% compared to the best baseline approach (STGAT).

The visualization of some testing cases is provided in Figure 6. Our framework can generate accurate and plausible trajectories. More specifically, in the top left case, for the blue prediction hypothesis at the left bottom, there is an abrupt change at the fifth prediction step. This is because the interaction graph evolved at this step. Moreover, in the heatmap, there are multiple possible trajectories starting from this point, which represent multiple potential modalities. These results show that the evolving interaction graph can reinforce the multi-modal property of our model since different samples of trajectories at the previous steps lead to different directions of graph evolution, which significantly influences the prediction afterwards. In the top right case, each car may leave the roundabout at any exit. Our model can successfully show the modalities of exiting the roundabout and staying in it. Moreover, if exiting the roundabout, the cars are predicted to exit on their right, which implies that the modalities predicted by our model are plausible and reasonable.

Summary and Broader Applications

We introduce EvolveGraph, a generic trajectory prediction framework with dynamic relational reasoning, which can handle evolving interacting systems involving multiple heterogeneous, interactive agents. The proposed framework could be applied to a wide range of applications, from purely physical systems to complex social dynamics systems. In this blog, we demonstrate some illustrative applications to physics objects and traffic participants. The framework could also be applied to analyze and predict the evolution of larger interacting systems, such as complex physical systems with a large number of interacting components, social networks, and macroscopical traffic flows. Although there are existing works using graph neural networks to handle trajectory prediction tasks, here we emphasize the impact of using our framework to recognize and predict the evolution of the underlying relations. With accurate and reasonable relational structures, we can forecast or generate plausible system behaviors, which help much with optimal decision making or other downstream tasks.

Acknowledgements: We thank all the co-authors of the paper “EvolveGraph: Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction with Dynamic Relational Reasoning” for their contributions and discussions in preparing this blog. The views and opinions expressed in this blog are solely of the authors.

This blog post is mainly based on the following paper:

EvolveGraph: Multi-Agent Trajectory Prediction with Dynamic Relational Reasoning

Jiachen Li*, Fan Yang*, Masayoshi Tomizuka, and Chiho Choi

Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (NeurIPS), 2020

Proceedings, Preprint, Project Website, Resources

Some other related works are listed as follows:

Conditional Generative Neural System for Probabilistic Trajectory Prediction

Jiachen Li, Hengbo Ma, and Masayoshi Tomizuka

IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Robotics and Systems (IROS), 2019

Proceedings, Preprint

Interaction-aware Multi-agent Tracking and Probabilistic Behavior Prediction via Adversarial Learning

Jiachen Li*, Hengbo Ma*, and Masayoshi Tomizuka

IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), 2019

Proceedings, Preprint

Generic Tracking and Probabilistic Prediction Framework and Its Application in Autonomous Driving

Jiachen Li, Wei Zhan, Yeping Hu, and Masayoshi Tomizuka

IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems, 2020

Article, Preprint

This article was initially published on the BAIR blog, and appears here with the authors’ permission.