ΑΙhub.org

RoboCup Logistics League: Interview with Sebastian Eltester

This year, RoboCup will be taking place from 22-28 June as a fully remote event with RoboCup competitions and activities taking place all over the world.

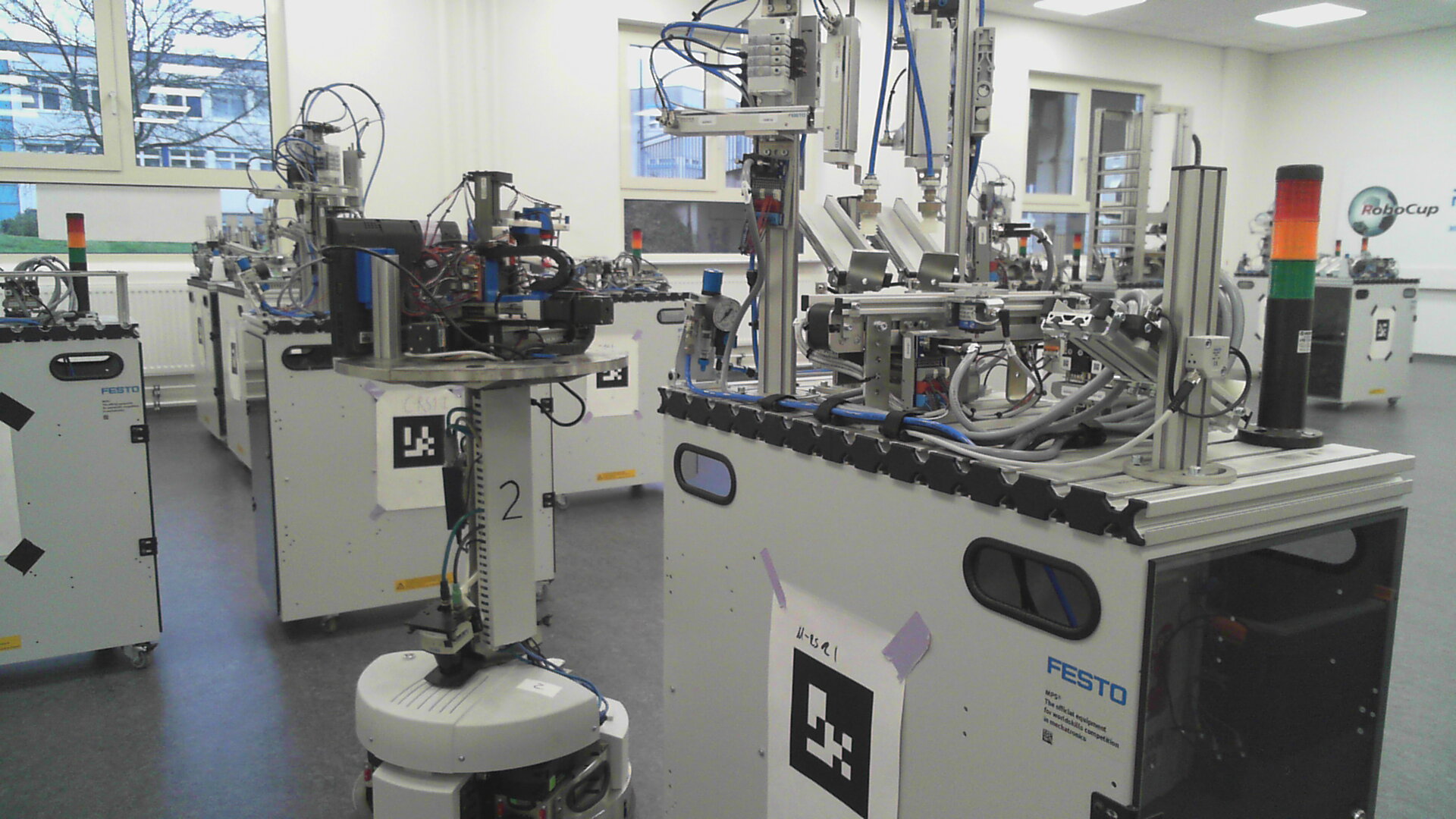

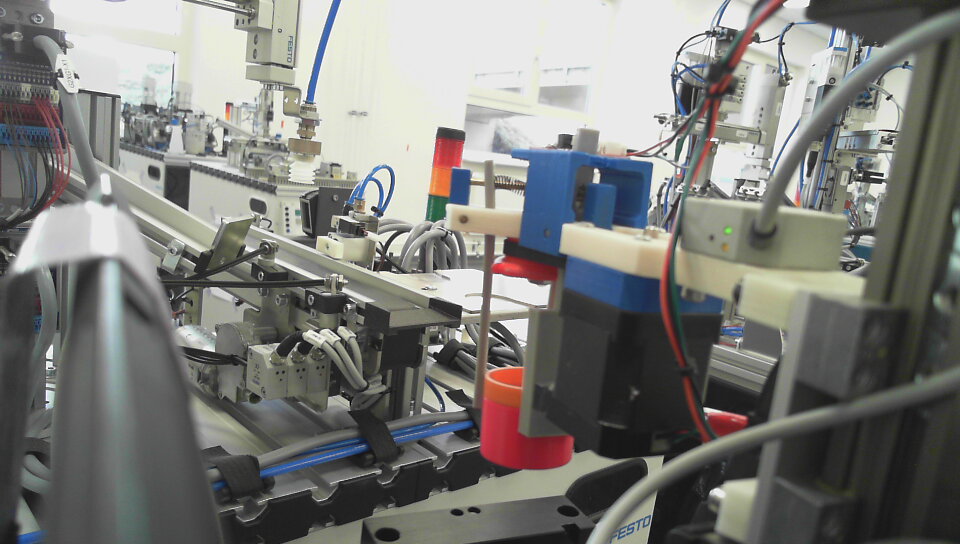

The RoboCup Logistics League (RCLL) is a sub-league of the RoboCup Industrial League. It focuses on in-factory logistics applications. The goal is for a team of autonomous robots to assemble products on demand, using a set of production machines.

Each team comprises up to three autonomous robots which can produce using seven machines. Each robot builds on a standardized robot platform which can be extended individually with sensors and computing devices. The robots are cooperative in the sense that they need to communicate and interact physically with the machines, e.g. fetching raw materials from a dispenser machine or delivering intermediate products to machines that refine them. In previous events, where the teams could compete in person, two teams shared a common factory floor.

A central agent (called Referee Box) randomly generates product orders with varying configurations and delivery windows. These orders are communicated to the robot teams that need to derive a production schedule and to distribute the tasks among the team robots.

We spoke to Sebastian Eltester, a member of the organising committee, about the league, how the competition will work, and the changes they’ve made to the event so that it can be held virtually.

Could you tell us about the tasks that the competitors have to complete?

On a very top level it’s a pick and place task. However, if you look further into the details, it suddenly becomes a task of very precise navigation and it also includes workpiece handling, mobile manipulation and planning.

Originally we started out as a planning and agent competition but we blew the whole thing open in 2015. Now, it’s a very general competition where you have to have mechanical engineers that do the design of your gripping equipment, and you need to have other competencies too, such as computer vision, for the navigation.

How has the competition changed this year?

This year we tried to split up our challenge into several smaller parts. We tried to organise the competition in a way that you don’t have to solve all of the tasks all at once – you can do them separately.

We effectively split it into three challenges:

- Navigation: the travelling salesman problem most accurately describes how we solve the navigation issues in our league. We have a production plan, but there is no set best way to solve it.

- Picking and placing: for the picking there are numerous ways to do this. There are some teams that have really interesting approaches for gripping objects.

- Production plan: here, the competitors get an order to fulfil.

We are trying to do something exciting and new this year with the competition. Due to the pandemic, and the fact that this is not a normal RoboCup year as such, we have a bit of freedom to try some things out. We felt like this is a golden opportunity to do these challenges. We hope this provides momentum that we can build upon. With these challenges you are not reliant on the production machines, which is usually one of the biggest hurdles. The machines are expensive.

Tell us more about the machines.

We actually use mock-up machines for the event. The mock-ups can be built out of wooden boxes with augmented reality (AR) tags on them. That is good enough to have a competition. We published some 3d models of the machine conveyor belt, shelves and slides so that people can 3d print these components, or make them out of wood. This way we can lower the barrier to entry for the teams. They don’t need a real machine, only a box. The only requirement is that it has to be an opaque material and has to roughly match the dimensions of the actual machine.

So, the teams use their own autonomous robots and combine with these mock-up machines for the challenges. Do the teams tend to use similar hardware or are their robots very different?

This is one of the things that I am passionate about and something that I really like about our league. There are actually major differences between the robots. Teams are very free in the hardware that they get to use.

For example, some of the teams have developed really elaborate gripping systems, based on a pneumatic gripper. There are also several teams that carry batteries around on top of their robots, some have CNC-machined parts. There are some really interesting design choices going on. Unfortunately, a lot of viewers don’t get to see the differences because all the robots are grey and everything looks the same. We haven’t found a good way to solve this yet. We can’t colour the machines due to the variety of sensors used in the league. Making a machine a different colour might interfere with sensors.

Compared to other agent and planning competitions, this aspect of real-world application is what sets us apart. We have to face all the real-world problems, such as wifi connection, subtle differences in the competition arenas, etc. This is something that I really enjoy about the league.

This is why we were hesitant to have a simulated league this year. We could have run the competition using a simulator that we have. However, It’s not who we are. We tried to put together a challenge that allowed us to keep our identity as a league. This real-world application is really what adds the extra spice for us.

How has the competition evolved over the years?

Currently, the game is split into two phases: an exploration phase and a production phase. The initial motivation behind the exploration phase was to tackle the issue that in a dynamic industry setting you wouldn’t have a fixed production line, like the Ford model, for example. In new industries, it’s very flexible. If a machine doesn’t fit the production process anymore you can move it somewhere else. The autonomous robot is smart enough to realise that the machine changed its place and searches for it somewhere else.

Over the years we’ve reached a place where we have sufficiently solved that issue. Now we have put a challenge together where we are merging the two phases. There is no exploration phase as such, the competitors can go out onto the field and do whatever they want. The motivation being that we want to check out how much knowledge of the world you need to successfully compete or even start a production process. You don’t need every machine for every single product that you build.

What else will be different this year?

This year we are going to try out a workshop. This is going to be a guided interaction with the system: this is a good way for us to inform the general public about the technology. They can see what things might look like in the future when this technology gets used.

As an additional challenge for some of the advanced teams, we’re going to showcase the whole production process, using the set-up in our lab. That way people will be able to see how the full game would be played.

How will the event work in the virtual environment?

For the competition, the teams will have to publish a schedule of what they are going to do during the day. Due to conflicting time zones, we cannot have a central live stream. We’ll have live streams where everybody can tune in, and we’ll have recorded versions of those streams to use as peer-reviews. We have a Referee Box (refbox) which will record everything that happens during the game. We can look at the logs from the refbox and compare them to the video stream: the two should match up.

We have our refbox set up in such a way that you can play an entire game using your own computer.

The teams will all have a streaming environment set up that at least shows everything that’s happening on the field of play. For interested viewers there should be some videos and streams to watch.

How many teams are there taking part?

This year there will be six teams taking part. There are three Japanese Teams: BabyTigers, WhiteLobster and NaraSuzaku, an Austrian team: GRIPS, Team Solidus from Switzerland and my own team, Carologistics, from Germany.

NaraSuzaku and WhiteLobster are teams from high schools, while the rest of the teams are comprised of university students and staff.

How many members are there in each team, roughly?

For our team, this usually fluctuates around 10 people. We are by far the largest team. The other teams usually consist of four to five core members.

When we are allowed to meet for events in person again, do you think you’ll stick with some of the virtual elements of the competition?

Personally, I would like to stick with some of the virtual elements. It is a really nice way to get people into the league. The other thought is that we could separate the virtual and competition elements of the competition.

Find out more

RoboCup 2021 event website.

Logistics League website.

tags: RoboCup, RoboCup2021