ΑΙhub.org

#AAAI2023 invited talk: Tuomas Sandholm on organ exchanges

Tuomas Sandholm is the winner of the 2023 AAAI Award for Artificial Intelligence for the Benefit of Humanity. This award recognizes positive impacts of artificial intelligence to protect, enhance, and improve human life in meaningful ways. Tuomas delivered an invited talk at the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, during which he spoke about the work that won him the award – using algorithms for organ exchanges.

Kidney disease is becoming more prevalent in the world, and, in the USA alone, over 90,000 people are waiting for a kidney transplant. This waiting list keeps growing year on year. The two routes for transplant are to receive a kidney from a deceased person, or via live donation. This second option has benefits including, on average, a shorter waiting time, and a healthier, longer-lasting kidney.

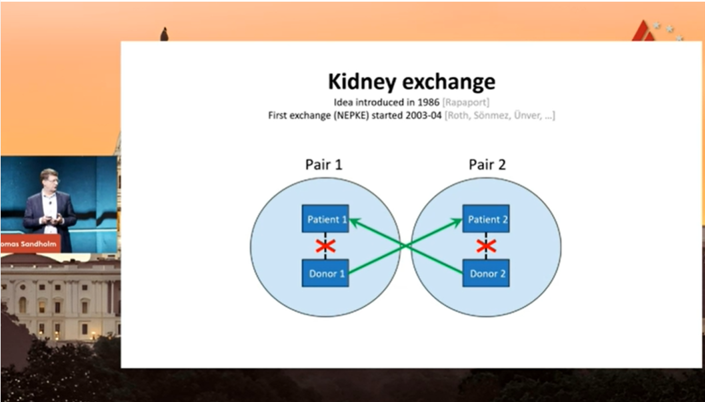

Typically, a patient participating in the live exchange method will receive an offer of donation from a relative or close friend. However, often these two people will not be compatible, due to different blood type or antibody incompatibility. Historically, these donors would have been turned away and the patient would lose the opportunity to receive a transplant. However, the concept of kidney paired donation (KPD), introduced by Rapaport in 1986, changed all that. Using this approach, patients with incompatible donors swap kidneys to receive a compatible kidney (see figure below).

Tuomas introducing the idea of kidney exchange.

Tuomas introducing the idea of kidney exchange.

This is an example of what is called a barter exchange. In this particular exchange “market”, patients seek to swap their incompatible donors with each other. These swaps consist of cycles of patients, and each patient receives the donation of another patient in the same cycle. In 2007, Tuomas and colleagues published a paper outlining a novel optimal branch-and-price algorithm for barter exchanges, with special focus on the USA kidney-exchange market. The objective of the problem is to maximise the weight combination of short, disjoint cycles in a pool (which could include hundreds of patients) of potential donor-patient pairs. The weights connect each pair (p) and represent the utility of pi receiving a kidney from pj. The cycles should be disjoint and short due to the logistics of the problem. All kidney exchange operations in a cycle should take place at the same time, and keeping the number of simultaneous operations to a minimum ensures that fewer people are affected if one part of the cycle fails. In practice, the cap on the cycle length is typically three.

This algorithm developed by Tuomas and his colleagues enabled the national kidney exchange in the USA, with the system going live in 2010. It is now used by 80% of the transplant centres in the USA, and, every week, the algorithm autonomously makes a plan for those transplant centres.

Altruistic donors

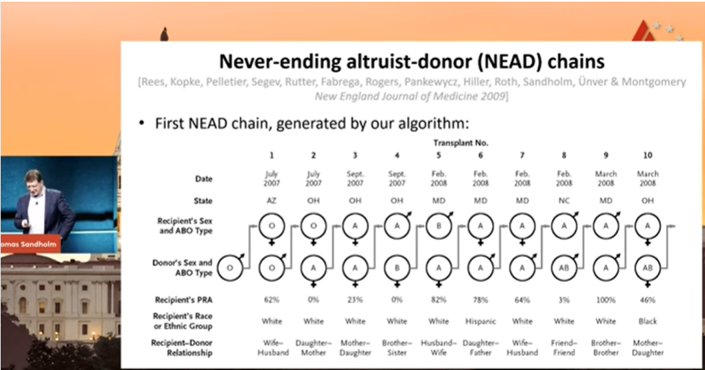

The next step for Tuomas and his team was to consider the case of altruistic donors; people who are prepared to donate a kidney for nothing in return. You can see an example of how this would work in the figure below. The initial altruistic donor starts a chain of donations, and there is a “left-over” donor which then becomes the start of the next chain of donations. These chains are known as never-ending altruist-donor (NEAD) chains and have become the main modality of kidney exchange worldwide. The benefits of this chain method is that the transplants don’t have to be carried our simultaneously, they can be done in segments. However, it is still beneficial to cap the chain length in case one link fails. The ideal scenario is to have many chains existing in parallel. Tuomas and his colleagues have developed a number of different algorithms for optimising this many-chain, or batch, problem. The latest of these is a position-indexed chain-edge formulation and was published here.

An example of a NEAD chain from Tuomas’ talk.

An example of a NEAD chain from Tuomas’ talk.

Failure-aware kidney exchange

Typically, only 7-12% of planned transplants are actually carried out. There are multiple reasons for this, but in terms of the process, it essentially means that in ~90% of cases, one “link” in the chain or cycle fails. To try to improve the success rate, Tuomas proposed a model where both weights and success probabilities are considered. To facilitate the solution, he used a branch-and-price algorithm in a probabilistic setting. This probabilistic approach turns out to be much more successful than the traditional approach; in fact, it can lead to twice as many transplants. This is because the model comes up with more robust solutions that proactively consider potential failures and how to avoid them.

Fairness

In the context of kidney exchange, there has been a lot of work into fairness, and how one decides who is prioritised over who in the transplant waiting list.

Tuomas advocated for pre-design ethics, where all of the discussion about the ethics of a system happens before the design itself. A human team of experts decides on the objective and the weights and feeds those into the policy design system. For example, in the case of kidney transplants, the objective could be to maximise the number of transplants, or to maximise the total survival years of the patients involved, or some such other objective. The model then gives the best policy, for the ethics that the domain experts wanted.

Future research

Tuomas closed his talk with a look ahead to some planned future research avenues. One particularly interesting project that he hopes to start shortly concerns reoptimizing the USA deceased heart donor allocation policy. He plans to apply the ideas of automated policy optimisation that he has used for this kidney research.

tags: AAAI, AAAI2023