ΑΙhub.org

Are emergent abilities of large language models a mirage? – Interview with Brando Miranda

Rylan Schaeffer, Brando Miranda, and Sanmi Koyejo won a NeurIPS 2023 outstanding paper award for their work Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage?. In their paper, they present an alternative explanation for emergent abilities in large language models. We spoke to Brando about this work, their alternative theory, and what inspired it.

Firstly, could you define what emergence is and what it means in the context of large language models?

This is a good and hard question to answer cleanly because the word emergence has been around in science for a while. For example, in physics, when you reach a certain number of uranium atoms you can make a bomb, but with fewer than that you can’t.

There are different definitions of emergence, but I think it would be helpful to say how we define it in our work. It is basically an unpredictable and sharp jump in some metric as some complexity parameter increases, usually the number of parameters. In the context of large language models this means that the model in question apparently goes from being inept to being really good at something.

That is what we studied in our work, and we showed basically that the jump is a big function of the metric, i.e how you score the model’s performance.

In the paper you call into question this claim that LLMs possess emergent abilities. What was it that made you want to investigate this further? What was the source of your initial doubt?

I’m quite a sceptical person and I really like to understand things well. I was lucky enough to be working with Rylan (who was in my lab on a rotation, and who should get credit for the idea and testing) and Samni, and our personalities worked perfectly for doing this kind of research. Rylan and I had both been thinking about this problem and, through our conversations, we converged on this research direction. As the evidence got more solid, we pursued it further. It was an iterative process, we had multiple hypotheses and the reason we got the paper out is because we were effective at iterating over a subset of them.

We were also taking a class, and the professors were talking about emergent abilities and there was a lot of back and forth with questions – with Rylan leading the discussion. We didn’t really believe it, I guess. We weren’t satisfied with the answers. I’ve never been shy about asking questions, and now that we are grad students, that type of questioning personality has paid off. We’re also passionate about the truth.

Could you talk a bit about your model?

The model is actually super simple. We sat down and wrote out what accuracy means and, assuming scaling laws (as the model gets bigger the cross entropy gets smaller), what we found was that, for a single token, you could have a closed-form equation if the sequence was of length 1. In other words, you could say accuracy equals the exponential of the negative cross entropy. The model suggested that these sharp, unpredictable jump will naturally occur because of the exponential.

The length L > 1 case is one of the most important cases and the one we emphasize and study in depth in the paper. However, I personally thought it was fascinating that even for length L=1 accuracy could be modeled by an exponential function of the scaling law/CE(N). In other words, the mathematical model suggests that sharp and predictable jumps happen even when the length of the sequence is 1. What we showed further is that in the case of LLMs (or models that output sequences) is that that is exacerbated because you’re shrinking something exponential even further by multiplying the exponential multiple times. So, for length 1, when you should expect sharp unpredictable jumps, for length > 1 it should be even worse. This is how people use LLMs in practice. It basically means it’s an intrinsic property of the metric, which I thought was interesting. In hindsight I guess it’s easier to think about it this way, but accuracy basically scores your model 0 or 1. In hindsight it sort of makes sense that accuracy is harsh because it is literally a step function. Some very simple math demonstrated that that’s probably true.

How did you go about testing your model? What experiments did you carry out?

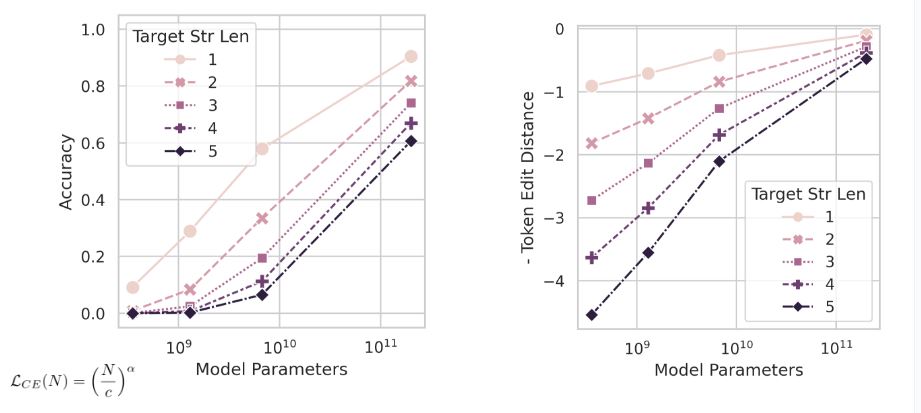

Once we had accuracy equals exponential of minus cross entropy as a function of the number of parameters, we got curves of accuracy versus parameters. The model is basically accuracy as a function of parameters. So, we plotted the mathematical model, and we can see how the curves of accuracy behave as the number of parameters increase. We also have multiple curves to show the dependence as a function of the length of the model.

We started with our mathematical plot and investigated if we could reproduce that plot for the LLM. And we could.

Example plot. Changing the metric leads to a linear plot (instead of the sharp jumps claimed as “emergence”).

Example plot. Changing the metric leads to a linear plot (instead of the sharp jumps claimed as “emergence”).

In the paper you mention that you have induced seemingly emerging abilities across various vision tasks by intentionally changing the metrics used for evaluation. Could you talk a bit about that?

Basically, we wanted to hammer home the point that by changing the metric you could accidentally create the plot that you wanted to, showing supposed emergent properties. When we experimented with autoencoders, we tried to mimic what the metrics that were being used to evaluate large language models were doing, but for vision. We had a task where there was a threshold where, once you had more than a certain number of pixels right, more or less, you got a score of one or zero, like a threshold function. It was like an interventional experiment; we change one variable and we show that it causes the changes.

This is actually a nice way to connect the entire paper. So, in the first half of the paper we have LLMs, we show our mathematical model and that it predicts sharpness. This is how the models behave; they do have sharpness. We also test our mathematical model for soft metrics (i.e. not using accuracy) and show that the LLMs do look smooth and linear-ish. Basically, we tested in the direction of harsh to soft and showed that the sharp jump went away.

In the second part of the paper, where we talk about vision, we did the reverse. Interestingly, in vision there is sort of an implicit agreement that we don’t see emerging abilities. Now we had our hypothesis we looked at the metrics they used, and we did the reverse experiment – from soft metrics to hard metrics. And we were able to “cause” emergent abilities.

What are the key messages that you want people to take away from your work?

I think it’s good to know which metrics you really care about in your application, but it’s also very important to understand the tradeoffs that they have. Accuracy is often the metric that people want to use, but either they don’t have enough test data or it’s just an intrinsically sharp, unstable metric and people don’t know about that. A good solution could be for people to come up with metrics that are close to what they want, but that don’t have these properties. In that way, at least we can do science better. That’s one key message: be aware of the metrics and trade-offs and don’t be surprised if you see sharp jumps if your metric is only allowing credit if you get the exact string, for example. Be careful with the evaluation process you use!

There’s also a deeper, philosophical question about what intelligence means. The metric and the task implicitly define what we mean by intelligence, for what we mean by an ability. Arithmetic, for example, is a favorite task for testing models, and the feeling that if you don’t get every digit right you didn’t get the arithmetic right. But that’s not really how we score humans. When you are in high school and you forget to carry a one, you’ll still get credit. Many exams are partitioned into parts to give partial credit, because we don’t claim that a person doesn’t know how to do math if they make one mistake.

There is sometimes a tendency for some work to be overhyped, with an overclaiming of results. I’m not sure that this is productive. I hope that this work will inspire people to be more sceptical about what they see reported.

Find out more

- Talk about the work on YouTube: Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage? – IEEE @ Stanford University

- The paper: Are Emergent Abilities of Large Language Models a Mirage?, Rylan Schaeffer, Brando Miranda, and Sanmi Koyejo.

About Brando

|

Brando Miranda is a current Ph.D. Student at Stanford University under the supervision of Professor Sanmi Koyejo in the Department of Computer Science at Stanford at the STAIR (Safe and Trustworthy AI) research group. Miranda’s research interests lie in data-centric machine learning for foundation models, meta-learning, machine learning for theorem proving, and human & brain-inspired Artificial Intelligence (AI). |

tags: NeurIPS, NeurIPS2023