ΑΙhub.org

Learning from logical constraints with lower- and upper-bound arithmetic circuits

How can we train neural networks efficiently to be more consistent with background knowledge?

Neural networks are remarkably good at recognising patterns in data, from images to language, but they often fail to respect rules and relationships that are obvious to humans. For instance, a neural network may learn to recognise road agents, their action, and their position in road scenes, yet struggle to consistently learn that “if an agent is crossing, it must be a pedestrian or a cyclist” or that “a traffic light cannot be red and green at the same time” [Giu+23] (see Figure 1).

Figure 1: Image of road scene in which a traffic light is detected as a “traffic light” (TL), a “red traffic light” (RedTL), and a “green traffic light” (GreenTL), which is not consistent with the general knowledge of road traffic.

Figure 1: Image of road scene in which a traffic light is detected as a “traffic light” (TL), a “red traffic light” (RedTL), and a “green traffic light” (GreenTL), which is not consistent with the general knowledge of road traffic.

To make AI systems more consistent with domain knowledge, without requiring large, labelled datasets, deep learning (which handles perception) can be combined with symbolic logic (which enforces structure and reasoning). This hybrid approach belongs to the field of neuro-symbolic AI (NeSy).

To use such background knowledge effectively, the symbolic constraints need to be connected to the network’s continuous outputs. The key idea is to turn logical rules into computable signals that indicate how well the network’s predictions comply with the knowledge, so these signals can be used as feedback during training.

In practice, logical formulas are used to evaluate how well the neural network’s predictions respect the domain constraints. In our work, the network outputs a probability for each literal present in the formula, and these probabilities are interpreted as weights for the corresponding literals. A reasoning engine then computes the degree of satisfaction of the logical formulas, effectively measuring how consistent the predictions are with the background knowledge.

During training, this satisfaction score is compared to a desired target value, and the resulting error is propagated back through the logical and neural components. This enables end-to-end learning, where the network gradually adjusts its parameters to produce predictions that are more logically consistent [Man+18].

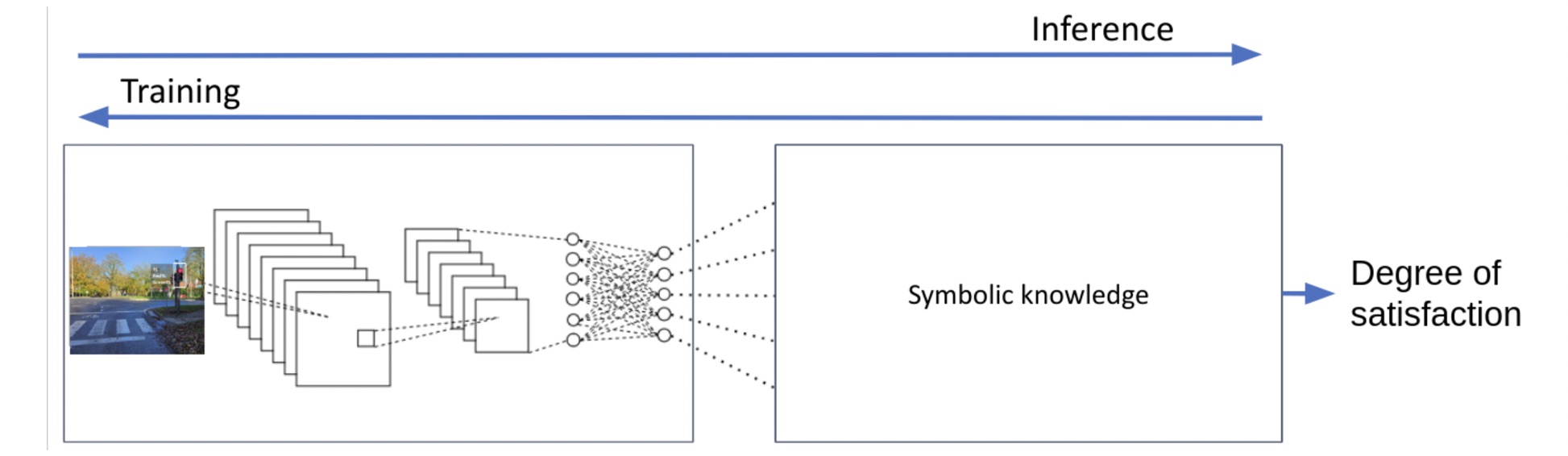

In the road traffic example, the network predicts probabilities for each agent’s identity, action and position. At inference, logical rules are evaluated using these predictions. The resulting satisfaction degree is then used to update the network so that future predictions better align with the knowledge constraints, as illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Considered pipeline between the neural and logical components for training and inference.

Figure 2: Considered pipeline between the neural and logical components for training and inference.

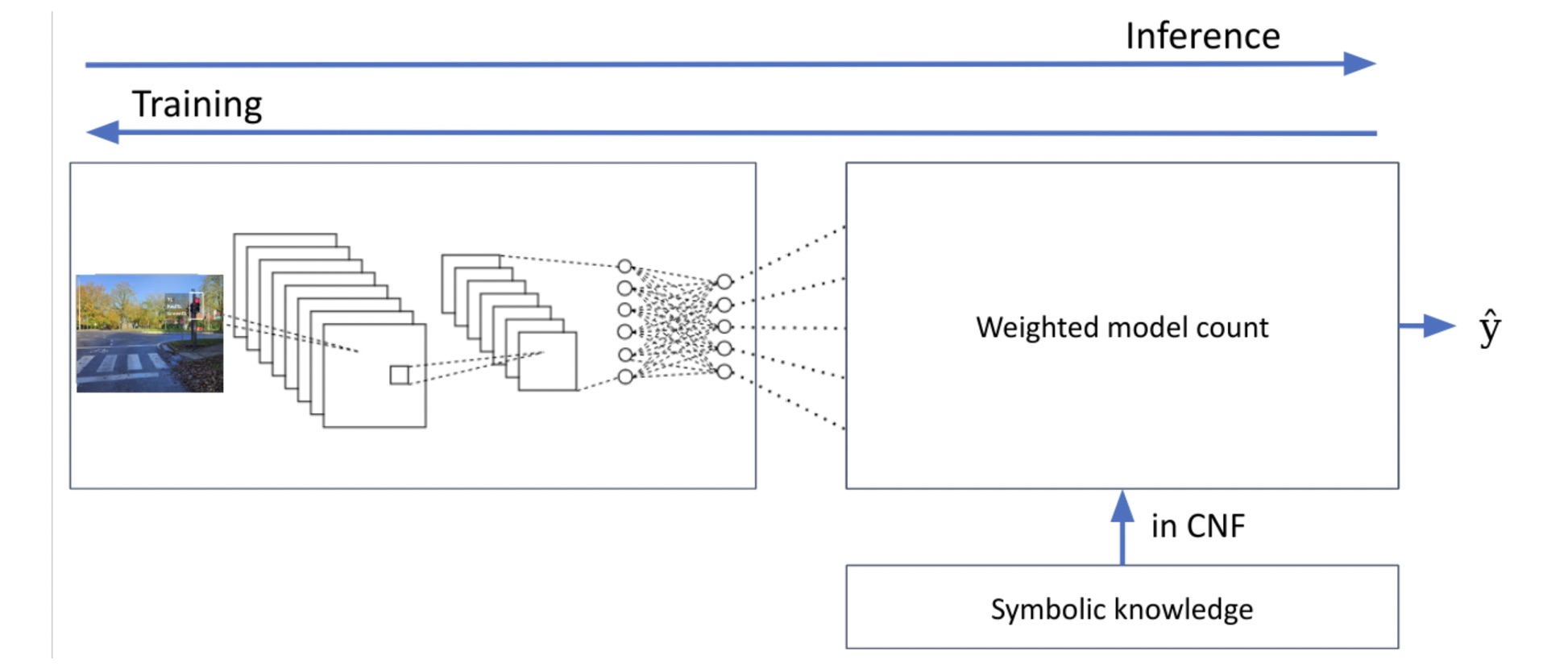

A key step in this process is computing this degree of satisfaction (and its gradient) efficiently. In many approaches, this computation relies on Weighted Model Counting (WMC) [CD08] (see Figure 3), which sums up the weights of all satisfying assignments of a logical formula.

Figure 3: Updated pipeline in which the degree of satisfaction of the logical formula is computed using the weighted model counting.

Figure 3: Updated pipeline in which the degree of satisfaction of the logical formula is computed using the weighted model counting.

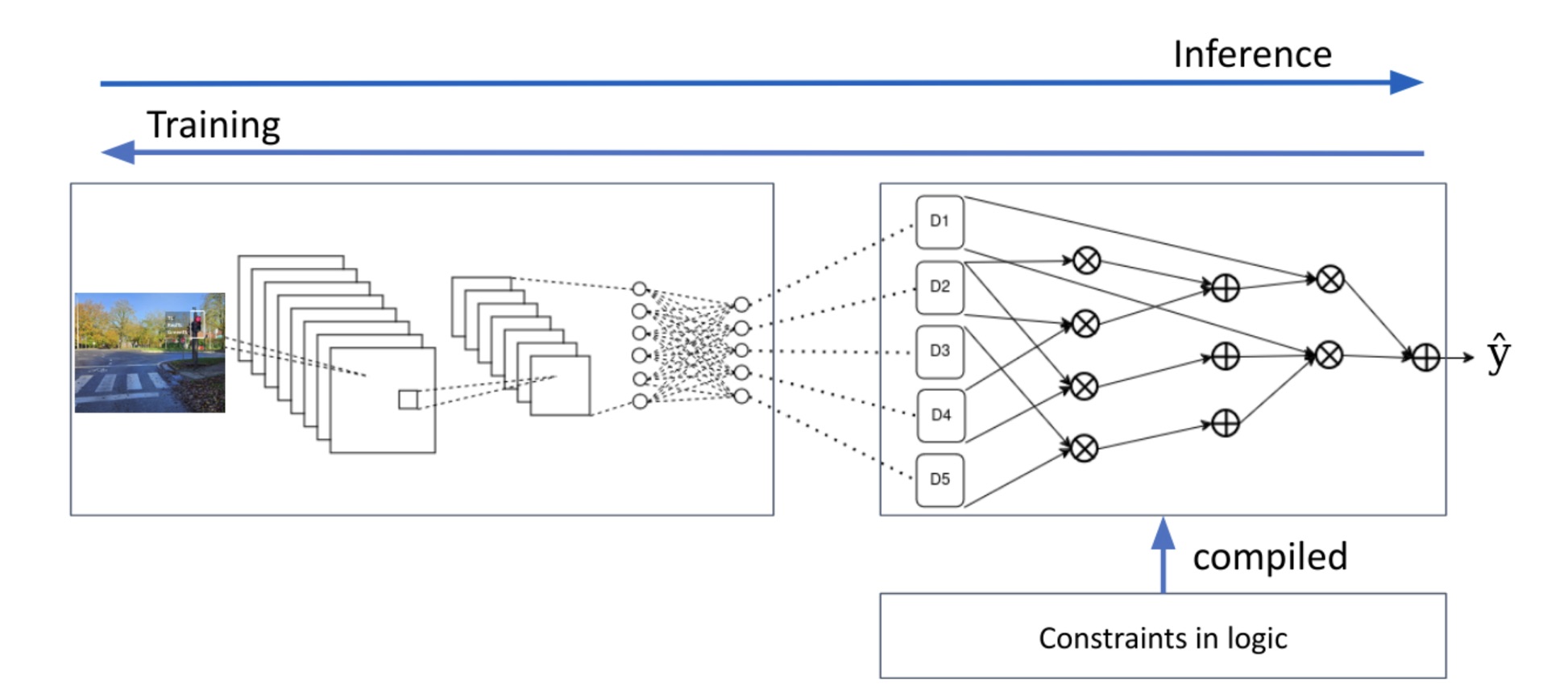

Computing the true WMC is a challenging task as it requires counting the number of solutions to a NP-hard problem. Moreover, this task must be done thousands of times (i.e., at each epoch of the training process). To make this computation efficient, WMC is typically implemented via knowledge compilation [DM02], transforming a logical formula into an arithmetic circuit (AC). These circuits can be evaluated from bottom-up to compute the WMC and can be differentiated from top-down to propagate gradients back into the neural network, as illustrated in Figure 4.

Figure 4: Updated pipeline in which the weighted model counting can be efficiently and repeatedly computed using knowledge compilation, transforming the formula into an arithmetic circuit.

Figure 4: Updated pipeline in which the weighted model counting can be efficiently and repeatedly computed using knowledge compilation, transforming the formula into an arithmetic circuit.

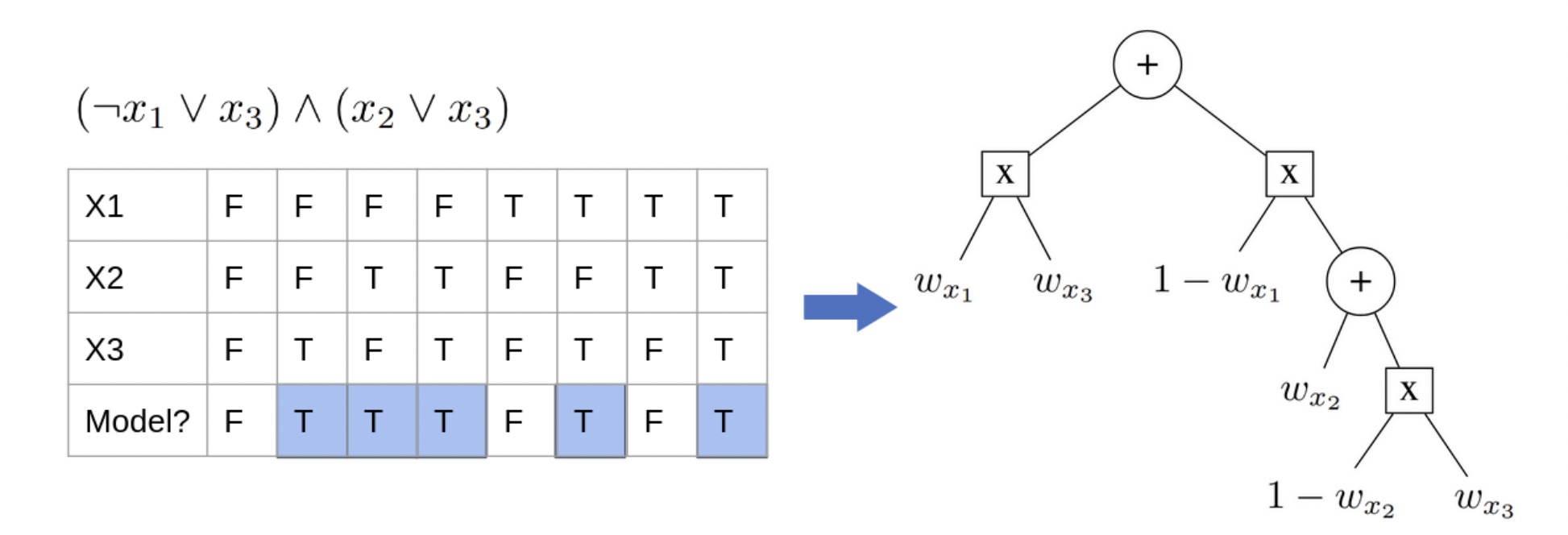

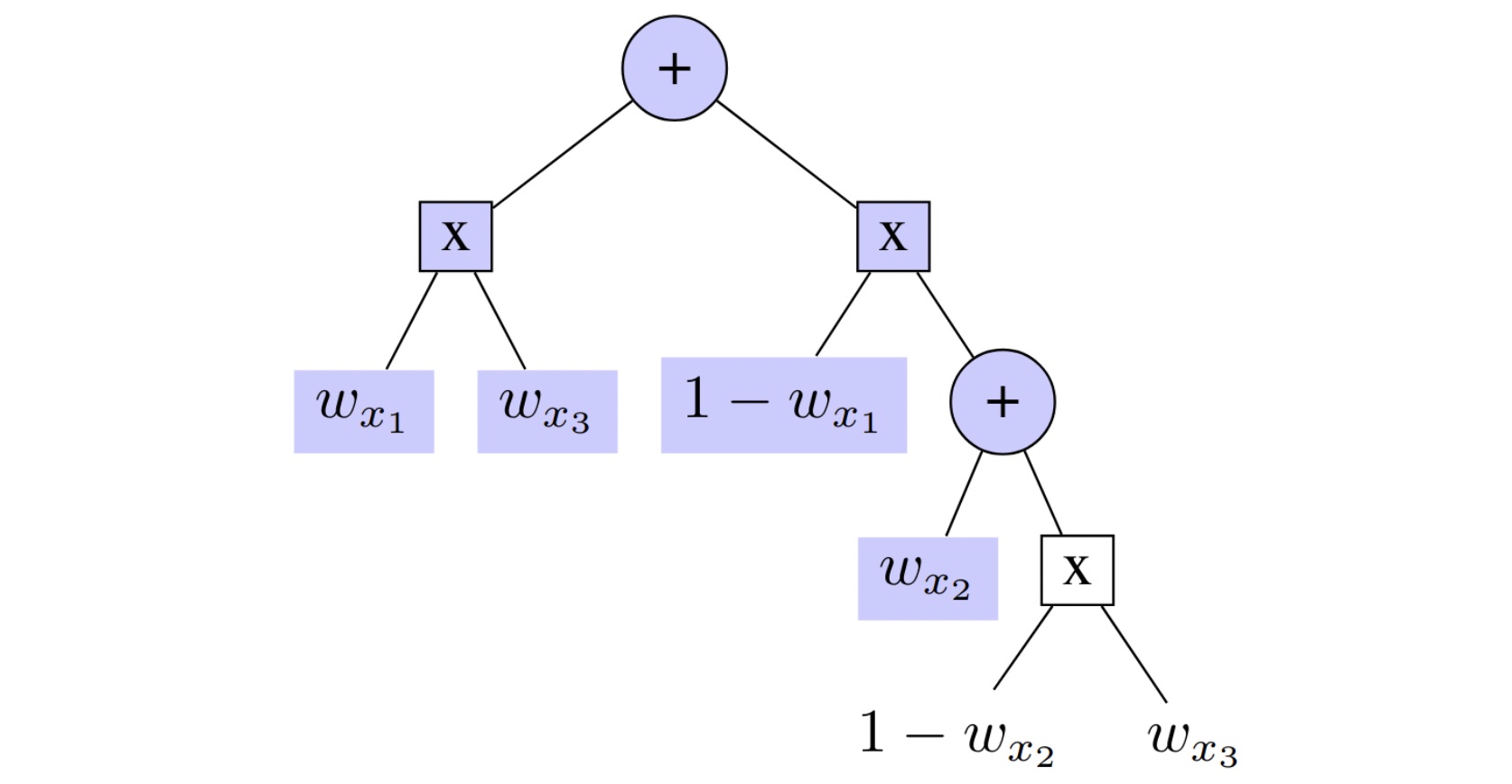

As an example, the logical formula (¬x1∨x3) ∧ (x2∨x3) can be compiled into an AC, computing exactly his WMC, as in Figure 5:

Figure 5: A formula and its corresponding truth table (left) compiled into an arithmetic circuit (right), computing its weighted model count.

Figure 5: A formula and its corresponding truth table (left) compiled into an arithmetic circuit (right), computing its weighted model count.

The problem: when logic becomes too hard to evaluate

Unfortunately, computing WMC, and compiling formulas into arithmetic circuits, is known to be a #P-hard problem [Val79], i.e., a problem in which the number of solutions of a NP-hard problem must be counted. Hence, for complex or large logical formulas, full compilation can be prohibitively expensive.

To deal with this, some earlier studies have proposed using partial circuits that cover only a subset of all possible satisfying assignments [MMD21]. These yield an approximate, lower-bound on the true WMC [Vla+16]. As an example, a possible lower-bound partial circuit for formula (¬x1∨x3) ∧ (x2∨x3) is illustrated in Figure 6 and consist in only considering the coloured part of the exact circuit, leaving out a subset of the models of the formula.

Figure 6: Exact arithmetic circuit, for which the coloured nodes correspond to a partially compiled circuit, computing the lower bound of the true WMC.

Figure 6: Exact arithmetic circuit, for which the coloured nodes correspond to a partially compiled circuit, computing the lower bound of the true WMC.

However, we showed that, while such circuits may give accurate WMC values, their gradients can diverge significantly from the true ones, even reversing the direction of some gradients. This is of course not desirable in a learning setting.

Our recent paper, presented at IJCAI 2025 [DDN25], addresses this limitation by introducing a framework that combines two complementary approximations in the Lower- and Upper-Bound Arithmetic Circuits (LUBAC) framework.

The idea: using both lower- and upper- bounds

Instead of relying on a single partial circuit, LUBAC introduces two complementary circuits:

- A lower-bound circuit (LB) – representing the subset of satisfying assignments already explored, as done in other works.

- An upper-bound circuit (UB) – representing information about the non-satisfying assignments encountered during partial compilation.

Together, these circuits bound the true probability of the logical formula. More importantly, by differentiating through both circuits, we can estimate gradients that are within a bounded error to the true gradients. The combination of both bounds provides more guarantees on the direction of the gradient when the underlying logic is only partially compiled than using a single lower-bound circuit.

How it works in practice

We implemented the LUBAC framework in Schlandals [DSN23], a weighted model counter developed at UCLouvain.

Our modification of this model counter stores additional information during partial search, allowing both the lower- and upper-bound circuits to be reconstructed afterwards. This post-processing adds negligible computational overhead.

We used our framework on the task of learning parameters of Bayesian networks, a well-known task in artificial intelligence. It has been shown that Bayesian networks can be transformed into weighted propositional formulas. Then, the task of learning its parameters can be reduced to learning the weights of the propositional formulas, which can be done in our framework. We varied the compilation timeouts, generating both small, partial circuits and more complete ones, and compared training using LB circuits alone, UB circuits alone, and both together.

What we found

- Controlled gradient direction. Using both lower- and upper-bound circuits provides more stable and reliable gradient directions. While using only lower- or upper-bound circuits may in some case provide better generalisation, there is much more variance in their results compared to the LUBAC framework.

- Negligible overhead. Generating both circuits added almost no extra runtime compared to compiling a single one.

- Approximation quality. The use of a lower- and upper-bound allows to quantify the range of values that the gradient can take, which can be used as an indication of the usefulness and quality of the current approximation level.

Limitations

- Reliance on compilation. Although LUBAC helps control gradient quality when learning under logical constraints, it still inherits the computational cost of model compilation. For complex formulas with large search spaces, producing tight lower- and upper-bound circuits can remain time-consuming.

- Gradient direction. While the framework guarantees that gradient errors are bounded, the approximate gradient may not always align perfectly with the true one, occasionally slowing or destabilising training.

- Bound tightness. The current bounds can sometimes be loose, indicating that further compilation or tighter bound computation could be beneficial.

What’s next

The LUBAC framework opens multiple research directions:

- Dynamic recompilation: updating circuits during training when the approximation gap grows.

- Smaller, faster circuits: trading off between size, accuracy, and training time.

- Integration with other NeSy systems: extending the experiments to complete neuro-symbolic pipelines to test the framework’s broader impact.

Links

Funding

This work was supported by Service Public de Wallonie Recherche under grant n°2010235 – ARIAC by DIGITAL- WALLONIA4.AI.

Sources

[CD08] M. Chavira and A. Darwiche. “On Probabilistic Inference by Weighted Model Counting”. In: Artificial Intelligence 172.6-7 (2008).

[DDN25] L. Dierckx, A. Dubray, and S. Nijssen. “Learning from Logical Constraints with Lower- and Upper-Bound Arithmetic Circuits”. In: International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence. 2025.

[DLL62] M. Davis, G. Logemann, and D. Loveland. “A machine program for theorem-proving”. In: Communications of the ACM 5.7 (1962), pp. 394–397.

[DM02] A. Darwiche and P. Marquis. “A knowledge compilation map”. In: Journal of Artificial Intelligence Research 17 (2002), pp. 229–264.

[DSN23] A. Dubray, P. Schaus, and S. Nijssen. “Probabilistic Inference by Projected Weighted Model Counting on Horn Clauses”. In: 29th International Conference on Principles and Practice of Constraint Programming (CP 2023). 2023.

[Fie+12] D. Fierens, G. V. d. Broeck, I. Thon, B. Gutmann, and L. De Raedt. “Inference in probabilistic logic programs using weighted CNF’s”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1202.3719 (2012).

[Giu+23] E. Giunchiglia, M. C. Stoian, S. Khan, F. Cuzzolin, and T. Lukasiewicz. “ROAD-R: the autonomous driving dataset with logical requirements”. In: Machine Learning 112.9 (2023), pp. 3261–3291.

[Man+18] R. Manhaeve, S. Dumancic, A. Kimmig, T. Demeester, and L. De Raedt. “Deepproblog: Neural Probabilistic Logic Programming”. In: advances in neural information processing systems 31 (2018).

[MMD21] R. Manhaeve, G. Marra, and L. De Raedt. “Approximate inference for neural probabilistic logic programming”. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on Principles of Knowledge Representation and Reasoning. IJCAI Organization. 2021, pp. 475–486.

[Scu09] M. Scutari. “Learning Bayesian networks with the bnlearn R package”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:0908.3817 (2009).

[Val79] L. G. Valiant. “The complexity of computing the permanent”. In: Theoretical Computer Science 8.2 (1979), pp. 189–201.

[Vla+16] J. Vlasselaer, A. Kimmig, A. Dries, W. Meert, and L. De Raedt. “Knowledge Compilation and Weighted Model Counting for Inference in Probabilistic Logic Programs.” In: AAAI Workshop: Beyond NP. Vol. 101. 2016.

tags: IJCAI, IJCAI2025