ΑΙhub.org

PICO: Pragmatic compression for human-in-the-loop decision-making

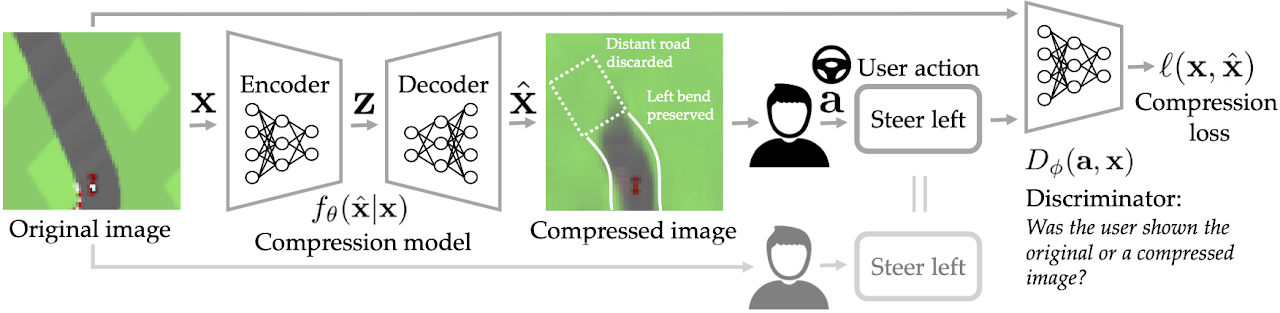

Fig. 1: Given the original image

Fig. 1: Given the original image ![]() , we would like to generate a compressed image

, we would like to generate a compressed image ![]() such that the user’s action

such that the user’s action ![]() upon seeing the compressed image is similar to what it would have been had the user seen the original image instead. In a 2D top-down car racing video game with an extremely high compression rate (50%), our compression model learns to preserve bends and discard the road farther ahead.

upon seeing the compressed image is similar to what it would have been had the user seen the original image instead. In a 2D top-down car racing video game with an extremely high compression rate (50%), our compression model learns to preserve bends and discard the road farther ahead.

Imagine remotely operating a Mars rover from a desk on Earth. The low-bandwidth network connection can make it challenging for the teleoperation system to provide the user with high-dimensional observations like images. One approach to this problem is to use data compression to minimize the number of bits that need to be communicated over the network: for example, the rover can compress the pictures it takes on Mars before sending them to the human operator on Earth. Standard lossy image compression algorithms would attempt to preserve the image’s appearance. However, at low bitrates, this approach can waste precious bits on information that the user does not actually need in order to perform their current task. For example, when deciding where to steer and how much to accelerate, the user probably only pays attention to a small subset of visual features, such as obstacles and landmarks. Our insight is that we should focus on preserving those features that affect user behavior, instead of features that only affect visual appearance (e.g., the color of the sky). In this post, we outline a pragmatic compression algorithm called PICO that achieves lower bitrates by intentionally allowing reconstructed images to deviate drastically from the visual appearance of their originals, and instead optimizing reconstructions for the downstream tasks that the user wants to perform with them (see Fig. 1).

Pragmatic compression

The straightforward approach to optimizing reconstructions for a specific task would be to train the compression model to directly minimize the loss function for that task. For example, if the user’s task is to classify MNIST digits, then one could train the compression model to generate reconstructions that minimize the cross-entropy loss of the user’s image classification policy. However, this approach requires prior knowledge of how to evaluate the utility of the user’s actions (e.g., the cross-entropy loss for digit labels), and the ability to fit an accurate model of the user’s decision-making policy (e.g., an image classifier). The key idea in our work is that we can avoid these limitations by framing the problem more generally: instead of trying to optimize for a specific task, we aim to produce a compressed image that induces the user to take the same action that they would have taken had they seen the original image. Furthermore, we aim to do so in the streaming setting (e.g., real-time video games), where we do not assume access to ground-truth action labels for the original images, and hence cannot compare the user’s action upon seeing the compressed image to some ground-truth action. To accomplish this, we use an adversarial learning procedure that involves training a discriminator to detect whether a user’s action was taken in response to the compressed image or the original. We call our method PragmatIc COmpression (PICO).

Maximizing functional similarity of images through human-in-the-loop adversarial learning

Let ![]() denote the original image,

denote the original image, ![]() the compressed image,

the compressed image, ![]() the user’s action,

the user’s action, ![]() the user’s decision-making policy, and

the user’s decision-making policy, and ![]() the compression model. PICO aims to minimize the divergence of the user’s policy evaluated on the compressed image

the compression model. PICO aims to minimize the divergence of the user’s policy evaluated on the compressed image ![]() from the user’s policy evaluated on the original image

from the user’s policy evaluated on the original image ![]() . Since the user’s policy

. Since the user’s policy ![]() is unknown, we approximately minimize the divergence using conditional generative adversarial networks, where the side information is the original image

is unknown, we approximately minimize the divergence using conditional generative adversarial networks, where the side information is the original image ![]() , the generator is the compression model

, the generator is the compression model ![]() , and the discriminator

, and the discriminator ![]() tries to discriminate the action

tries to discriminate the action ![]() that the user takes after seeing the generated image

that the user takes after seeing the generated image ![]() (see Fig. 1).

(see Fig. 1).

To train the action discriminator ![]() , we need positive and negative examples of user behavior; in our case, examples of user behavior with and without compression. To collect these examples, we randomize whether the user sees the compressed image or the original before taking an action. When the user sees the original

, we need positive and negative examples of user behavior; in our case, examples of user behavior with and without compression. To collect these examples, we randomize whether the user sees the compressed image or the original before taking an action. When the user sees the original ![]() and takes action

and takes action ![]() , and we record the pair

, and we record the pair ![]() as a positive example of user behavior. When the user sees the compressed image

as a positive example of user behavior. When the user sees the compressed image ![]() and takes action

and takes action ![]() , we record

, we record ![]() as a negative example. We then train an action discriminator

as a negative example. We then train an action discriminator ![]() to minimize the standard binary cross-entropy loss. Note that this action discriminator is conditioned on the original image

to minimize the standard binary cross-entropy loss. Note that this action discriminator is conditioned on the original image ![]() and the user action

and the user action ![]() , but not the compressed image

, but not the compressed image ![]() —this ensures that the action discriminator captures differences in user behavior caused by compression, while ignoring differences between the original and compressed images that do not affect user behavior.

—this ensures that the action discriminator captures differences in user behavior caused by compression, while ignoring differences between the original and compressed images that do not affect user behavior.

Distilling the discriminator and training the compression model

The action discriminator ![]() gives us a way to approximately evaluate the user’s policy divergence. However, we cannot train the compression model

gives us a way to approximately evaluate the user’s policy divergence. However, we cannot train the compression model ![]() to optimize this loss directly, since

to optimize this loss directly, since ![]() does not take the compressed image

does not take the compressed image ![]() as input. To address this issue, we distill the trained action discriminator

as input. To address this issue, we distill the trained action discriminator ![]() , which captures differences in user behavior caused by compression, into an image discriminator

, which captures differences in user behavior caused by compression, into an image discriminator ![]() that links the compressed images to these behavioral differences. Details can be found in Section 3.2 of the full paper.

that links the compressed images to these behavioral differences. Details can be found in Section 3.2 of the full paper.

Structured compression using generative models

One approach to representing the compression model ![]() could be to structure it as a variational autoencoder (VAE), and train the VAE end to end on PICO’s adversarial loss function instead of the standard reconstruction error loss. This approach is fully general, but requires training a separate model for each desired bitrate, and can require extensive exploration of the pixel output space before it discovers an effective compression model. To simplify variable-rate compression and exploration in our experiments, we forgo end-to-end training: we first train a generative model on a batch of images without the human in the loop by optimizing a task-agnostic perceptual loss, then train our compression model to select which subset of latent features to transmit for any given image. We use a variety of different generative models in our experiments, including VAE,

could be to structure it as a variational autoencoder (VAE), and train the VAE end to end on PICO’s adversarial loss function instead of the standard reconstruction error loss. This approach is fully general, but requires training a separate model for each desired bitrate, and can require extensive exploration of the pixel output space before it discovers an effective compression model. To simplify variable-rate compression and exploration in our experiments, we forgo end-to-end training: we first train a generative model on a batch of images without the human in the loop by optimizing a task-agnostic perceptual loss, then train our compression model to select which subset of latent features to transmit for any given image. We use a variety of different generative models in our experiments, including VAE, ![]() -VAE, NVAE, and StyleGAN2 models.

-VAE, NVAE, and StyleGAN2 models.

User studies

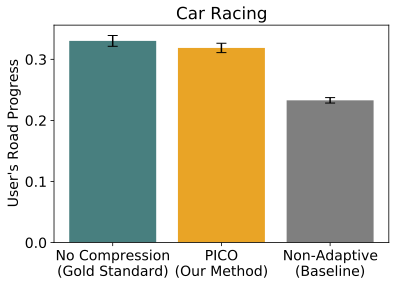

We evaluate our method through experiments with human participants on four tasks: reading handwritten digits, browsing an online shopping catalogue of cars, verifying photos of faces, and playing a car racing video game. The results show that our method learns to match the user’s actions with and without compression at lower bitrates than baseline methods, and adapts the compression model to the user’s behavior.

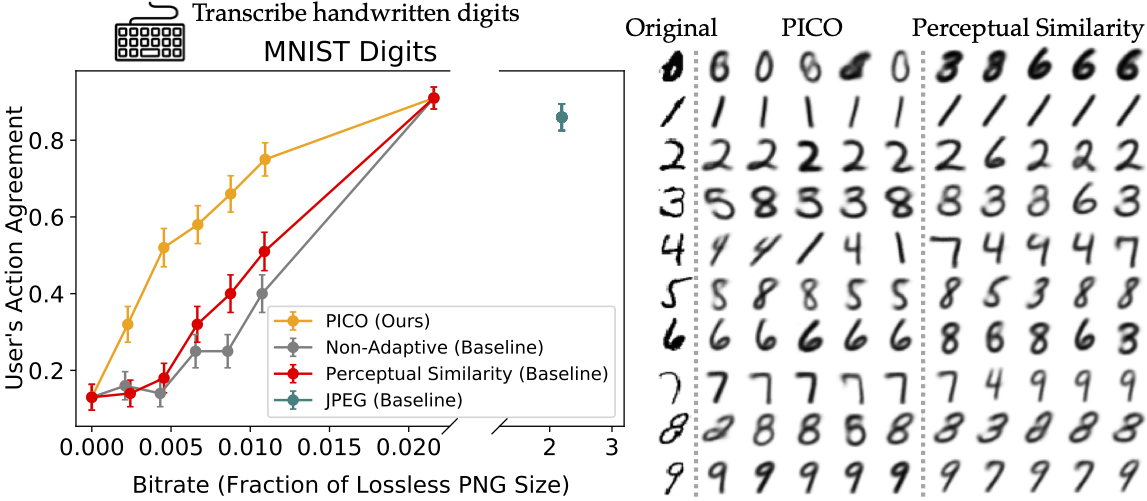

Transcribing handwritten digits

For users performing a digit reading task, PICO learned to preserve the digit number, while a baseline compression method that optimizes perceptual similarity learns to preserve task-irrelevant details like line thickness and pose angle.

Fig. 2: Left: the y-axis represents the rate of agreement of user actions (digit labels) upon seeing a compressed image with user actions upon seeing the original version of that image. Right: each of the five columns in the two groups of compressed images represents a different sample from the stochastic compression model

Fig. 2: Left: the y-axis represents the rate of agreement of user actions (digit labels) upon seeing a compressed image with user actions upon seeing the original version of that image. Right: each of the five columns in the two groups of compressed images represents a different sample from the stochastic compression model ![]() at bitrate 0.011.

at bitrate 0.011.

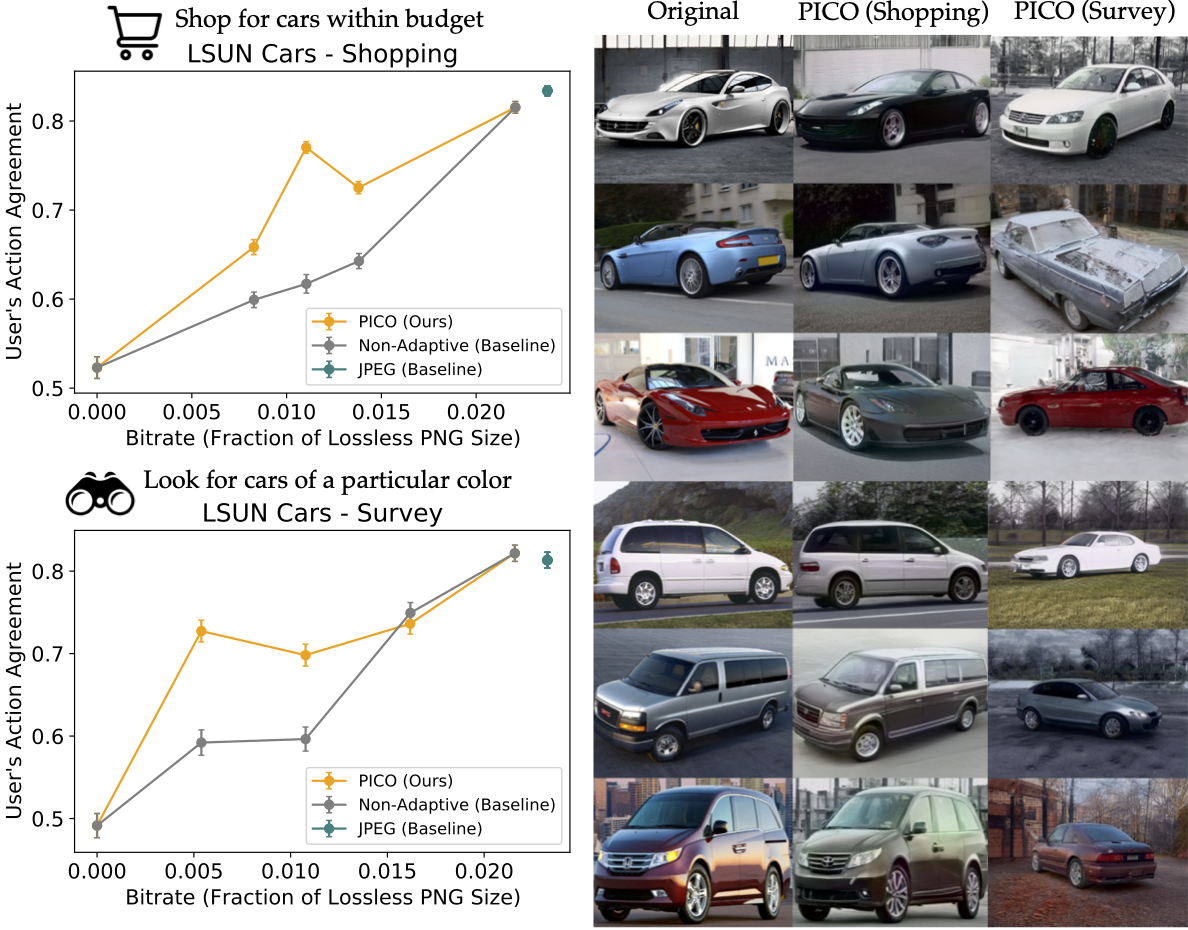

Car shopping and surveying

We asked one group of participants to perform a “shopping” task, in which we instructed them to select pictures of cars that they perceive to be within their budget. For these users, PICO learned to preserve the sportiness and perceived price of the car, while randomizing color and background.

Fig. 3

Fig. 3

To test whether PICO can adapt the compression model to the specific needs of different downstream tasks in the same domain, we asked another group of participants to perform a different task with the same car images: survey paint jobs (while ignoring perceived price and other features). For these users, PICO learned to preserve the color of the car, while randomizing the model and pose of the car.

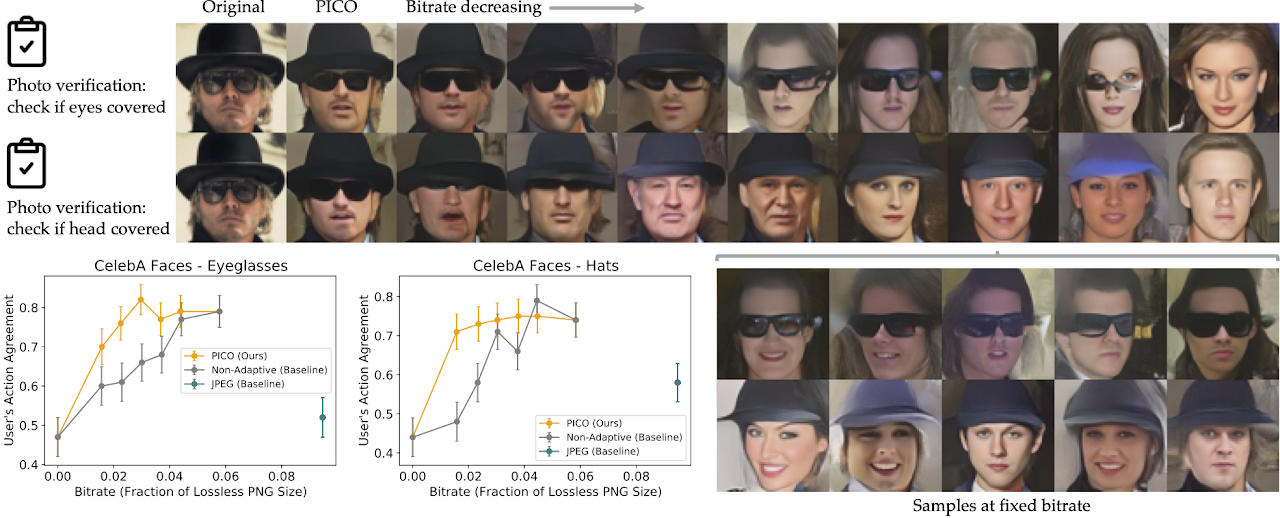

Photo attribute verification

For users performing a photo verification task that involves checking for eyeglasses, PICO learned to preserve eyeglasses while randomizing faces, hats, and other task-irrelevant features. When we changed the task to checking for hats, PICO adapted to preserving hats while randomizing eyeglasses.

Fig. 4

Fig. 4

Car racing video game

For users playing a 2D car racing video game with an extremely high compression rate (50%), PICO learned to preserve bends in the road better than baseline methods, enabling users to drive more safely and stay off the grass.

Fig. 5: Top: what is actually happening (uncompressed). Middle: what the user sees (compressed with PICO).

Fig. 5: Top: what is actually happening (uncompressed). Middle: what the user sees (compressed with PICO).

What’s next?

This work is a proof of concept that uses pre-trained generative models to speed up human-in-the-loop learning during our small-scale user studies. However, end-to-end training of the compression model may be practical for real-world web services and other applications, where large numbers of users already continually interact with the system. PICO’s adversarial training procedure, which involves randomizing whether users see compressed or uncompressed images, can be implemented in a straightforward manner using standard A/B testing frameworks. Furthermore, in our experiments, we evaluate on extremely high compression rates in order to highlight differences between PICO and other methods, which leads to large visual distortions—in real-world settings with lower compression rates, we would likely see smaller distortions.

Continued improvements to generative model architectures for video, audio, and text could unlock a wide range of real-world applications for pragmatic compression, including video compression for robotic space exploration, audio compression for hearing aids, and spatial compression for virtual reality. We are especially excited about using PICO to shorten media for human consumption: for example, summarizing text in such a way that a user who only reads the summary can answer reading comprehension questions just as accurately as if they had read the full text, or trimming a podcast to eliminate pauses and filler words that do not communicate useful information.

If you want to learn more, check out our pre-print on arXiv: Siddharth Reddy, Anca D. Dragan, Sergey Levine, Pragmatic Image Compression for Human-in-the-Loop Decision-Making, arXiv, 2021.

To encourage replication and extensions, we have released our code. Additional videos are available through the project website.

This article was initially published on the BAIR blog, and appears here with the authors’ permission.

tags: deep dive