ΑΙhub.org

Studying AI recruitment tools: race, gender, and AI’s “eradication of difference”

Philipp Schmitt & AT&T Laboratories Cambridge / Better Images of AI / Data flock (faces) / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

Philipp Schmitt & AT&T Laboratories Cambridge / Better Images of AI / Data flock (faces) / Licenced by CC-BY 4.0

Recent years have seen the emergence of AI tools marketed as an answer to lack of diversity in the workforce, from use of chatbots and CV scrapers to line up prospective candidates, through to analysis software for video interviews.

Those behind the technology claim it cancels out human biases against gender and ethnicity during recruitment, instead using algorithms that read vocabulary, speech patterns and even facial micro-expressions to assess huge pools of job applicants for the right personality type and ‘culture fit’.

However, in a new report published in Philosophy and Technology, researchers from Cambridge’s Centre for Gender Studies argue these claims make some uses of AI in hiring little better than an ‘automated pseudoscience’ reminiscent of physiognomy or phrenology: the discredited beliefs that personality can be deduced from facial features or skull shape.

They say it is a dangerous example of ‘technosolutionism’: turning to technology to provide quick fixes for deep-rooted discrimination issues that require investment and changes to company culture.

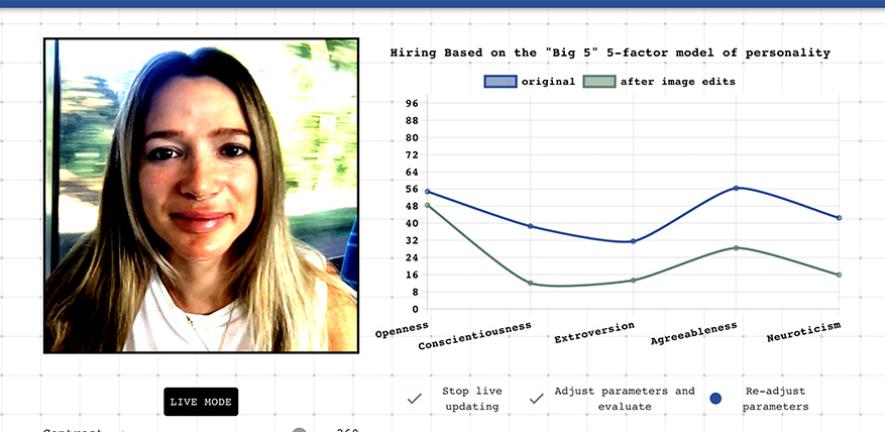

In fact, the researchers have worked with a team of Cambridge computer science undergraduates to debunk these new hiring techniques by building an AI tool modelled on the technology, available online.

The ‘Personality Machine’ demonstrates how arbitrary changes in facial expression, clothing, lighting and background can give radically different personality readings – and so could make the difference between rejection and progression for a generation of job seekers vying for graduate positions.

The Cambridge team say that use of AI to narrow candidate pools may ultimately increase uniformity rather than diversity in the workforce, as the technology is calibrated to search for the employer’s fantasy ‘ideal candidate’.

This could see those with the right training and background “win over the algorithms” by replicating behaviours the AI is programmed to identify, and taking those attitudes into the workplace, say the researchers.

Additionally, as algorithms are honed using past data, they argue that candidates considered the best fit are likely to end up those that most closely resembling the current workforce.

“We are concerned that some vendors are wrapping ‘snake oil’ products in a shiny package and selling them to unsuspecting customers,” said co-author Dr Eleanor Drage.

“By claiming that racism, sexism and other forms of discrimination can be stripped away from the hiring process using artificial intelligence, these companies reduce race and gender down to insignificant data points, rather than systems of power that shape how we move through the world.”

The researchers point out that these AI recruitment tools are often proprietary, or ‘black box’, so how they work is a mystery.

“While companies may not be acting in bad faith, there is little accountability for how these products are built or tested,” said Drage. “As such, this technology, and the way it is marketed, could end up as dangerous sources of misinformation about how recruitment can be ‘de-biased’ and made fairer.”

Despite some pushback – the EU’s proposed AI Act classifies AI-powered hiring software as ‘high risk’, for example – researchers say that tools made by companies such as Retorio and myInterview are deployed with little regulation, and point to surveys suggesting use of AI in hiring is snowballing.

A 2020 study of 500 organisations across various industries in five countries found 24% of businesses have implemented AI for recruitment purposes and 56% of hiring managers planned to adopt it in the next year.

Another poll of 334 leaders in human resources, conducted in April 2020, as the pandemic took hold, found that 86% of organisations were incorporating new virtual technology into hiring practices.

“This trend was in already in place as the pandemic began, and the accelerated shift to online working caused by COVID-19 is likely to see greater deployment of AI tools by HR departments in future,” said co-author Dr Kerry Mackereth, who presents the Good Robot podcast with Drage, in which the duo explore the ethics of technology.

COVID-19 is not the only factor, according to HR operatives the researchers have interviewed. “Volume recruitment is increasingly untenable for human resources teams that are desperate for software to cut costs as well as numbers of applicants needing personal attention,” said Mackereth.

Drage and Mackereth say many companies now use AI to analyse videos of candidates, interpreting personality by assessing regions of a face – similar to lie-detection AI – and scoring for the ‘big five’ personality tropes: extroversion, agreeableness, openness, conscientiousness, and neuroticism.

Co-author Dr Eleanor Drage testing the ‘personality machine’ built by Cambridge undergraduates. Credit: Eleanor Drage.

Co-author Dr Eleanor Drage testing the ‘personality machine’ built by Cambridge undergraduates. Credit: Eleanor Drage.

The undergraduates behind the ‘Personality Machine’, which uses a similar technique to expose its flaws, say that while their tool may not help users beat the algorithm, it will give job seekers a flavour of the kinds of AI scrutiny they might be under – perhaps even without their knowledge.

“All too often, the hiring process is oblique and confusing,” said Euan Ong, one of the student developers. “We want to give people a visceral demonstration of the sorts of judgements that are now being made about them automatically”.

“These tools are trained to predict personality based on common patterns in images of people they’ve previously seen, and often end up finding spurious correlations between personality and apparently unrelated properties of the image, like brightness. We made a toy version of the sorts of models we believe are used in practice, in order to experiment with it ourselves,” Ong said.

Read the research in full

Does AI Debias Recruitment? Race, Gender, and AI’s “Eradication of Difference”, Eleanor Drage & Kerry Mackereth.