ΑΙhub.org

Koala: A dialogue model for academic research

By Xinyang Geng, Arnav Gudibande, Hao Liu, Eric Wallace and Sergey Levine

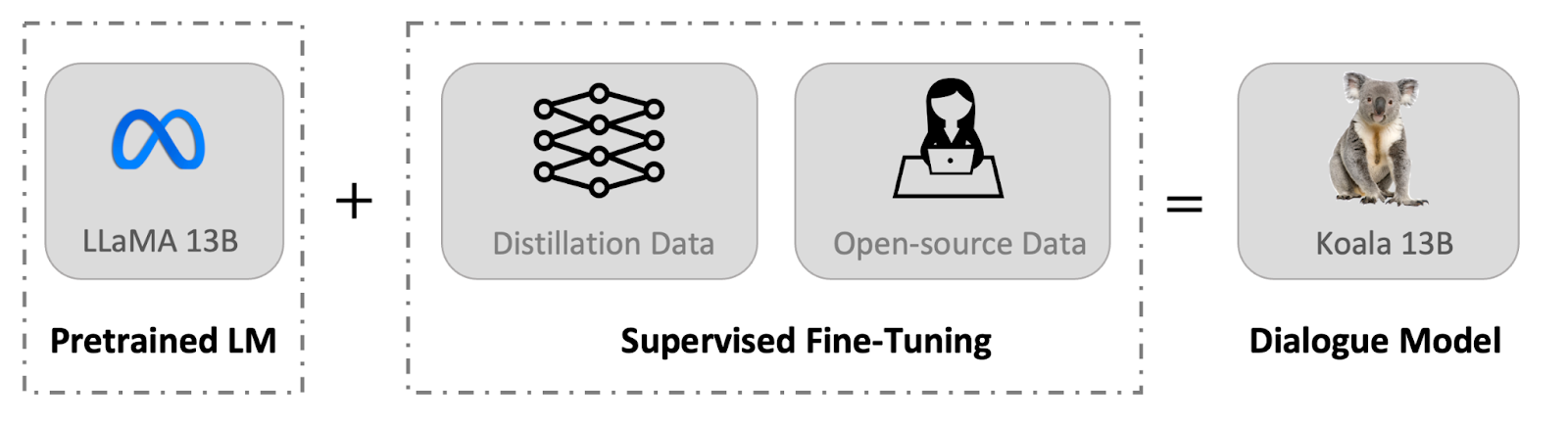

In this post, we introduce Koala, a chatbot trained by fine-tuning Meta’s LLaMA on dialogue data gathered from the web. We describe the dataset curation and training process of our model, and also present the results of a user study that compares our model to ChatGPT and Stanford’s Alpaca. Our results show that Koala can effectively respond to a variety of user queries, generating responses that are often preferred over Alpaca, and at least tied with ChatGPT in over half of the cases.

We hope that these results contribute further to the discourse around the relative performance of large closed-source models to smaller public models. In particular, it suggests that models that are small enough to be run locally can capture much of the performance of their larger cousins if trained on carefully sourced data. This might imply, for example, that the community should put more effort into curating high-quality datasets, as this might do more to enable safer, more factual, and more capable models than simply increasing the size of existing systems. We emphasize that Koala is a research prototype, and while we hope that its release will provide a valuable community resource, it still has major shortcomings in terms of content, safety, and reliability, and should not be used outside of research.

- Online interactive demo

- EasyLM: training and serving framework

- Koala model weights diff agaist base LLaMA

System overview

Large language models (LLMs) have enabled increasingly powerful virtual assistants and chat bots, with systems such as ChatGPT, Bard, Bing Chat, and Claude able to respond to a breadth of user queries, provide sample code, and even write poetry. Many of the most capable LLMs require huge computational resources to train, and oftentimes use large and proprietary datasets. This suggests that in the future, highly capable LLMs will be largely controlled by a small number of organizations, and both users and researchers will pay to interact with these models without direct access to modify and improve them on their own. On the other hand, recent months have also seen the release of increasingly capable freely available or (partially) open-source models, such as LLaMA. These systems typically fall short of the most capable closed models, but their capabilities have been rapidly improving. This presents the community with an important question: will the future see increasingly more consolidation around a handful of closed-source models, or the growth of open models with smaller architectures that approach the performance of their larger but closed-source cousins?

While the open models are unlikely to match the scale of closed-source models, perhaps the use of carefully selected training data can enable them to approach their performance. In fact, efforts such as Stanford’s Alpaca, which fine-tunes LLaMA on data from OpenAI’s GPT model, suggest that the right data can improve smaller open source models significantly.

We introduce a new model, Koala, which provides an additional piece of evidence toward this discussion. Koala is fine-tuned on freely available interaction data scraped from the web, but with a specific focus on data that includes interaction with highly capable closed-source models such as ChatGPT. We fine-tune a LLaMA base model on dialogue data scraped from the web and public datasets, which includes high-quality responses to user queries from other large language models, as well as question answering datasets and human feedback datasets. The resulting model, Koala-13B, shows competitive performance to existing models as suggested by our human evaluation on real-world user prompts.

Our results suggest that learning from high-quality datasets can mitigate some of the shortcomings of smaller models, maybe even matching the capabilities of large closed-source models in the future. This might imply, for example, that the community should put more effort into curating high-quality datasets, as this might do more to enable safer, more factual, and more capable models than simply increasing the size of existing systems.

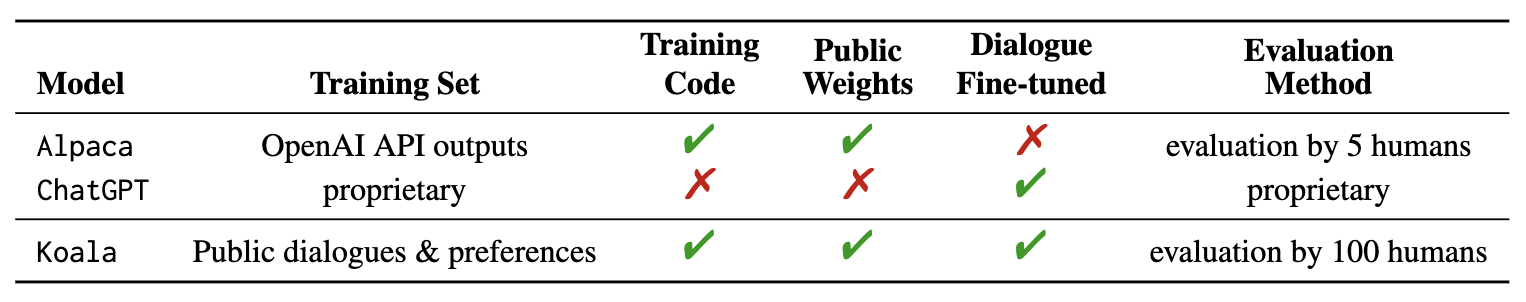

By encouraging researchers to engage with our system demo, we hope to uncover any unexpected features or deficiencies that will help us evaluate the models in the future. We ask researchers to report any alarming actions they observe in our web demo to help us comprehend and address any issues. As with any release, there are risks, and we will detail our reasoning for this public release later in this blog post. We emphasize that Koala is a research prototype, and while we hope that its release will provide a valuable community resource, it still has major shortcomings in terms of content, safety, and reliability, and should not be used outside of research. Below we provide an overview of the differences between Koala and notable existing models.

Datasets and training

A primary obstacle in building dialogue models is curating training data. Prominent chat models, including ChatGPT, Bard, Bing Chat and Claude use proprietary datasets built using significant amounts of human annotation. To construct Koala, we curated our training set by gathering dialogue data from the web and public datasets. Part of this data includes dialogues with large language models (e.g., ChatGPT) which users have posted online.

Rather than maximizing quantity by scraping as much web data as possible, we focus on collecting a small high-quality dataset. We use public datasets for question answering, human feedback (responses rated both positively and negatively), and dialogues with existing language models. We provide the specific details of the dataset composition below.

ChatGPT distillation data

Public User-Shared Dialogues with ChatGPT (ShareGPT) Around 60K dialogues shared by users on ShareGPT were collected using public APIs. To maintain data quality, we deduplicated on the user-query level and removed any non-English conversations. This leaves approximately 30K examples.

Human ChatGPT Comparison Corpus (HC3) We use both the human and ChatGPT responses from the HC3 english dataset, which contains around 60K human answers and 27K ChatGPT answers for around 24K questions, resulting in a total number of around 87K question-answer examples.

Open source data

Open Instruction Generalist (OIG). We use a manually-selected subset of components from the Open Instruction Generalist dataset curated by LAION. Specifically, we use the grade-school-math-instructions, the poetry-to-songs, and the plot-screenplay-books-dialogue datasets. This results in a total of around 30k examples.

Stanford Alpaca. We include the dataset used to train the Stanford Alpaca model. The dataset contains around 52K examples, which is generated by OpenAI’s text-davinci-003 following the self-instruct process. It is worth noting that HC3, OIG, and Alpaca datasets are single-turn question answering while ShareGPT dataset is dialogue conversations.

Anthropic HH. The Anthropic HH dataset contains human ratings of harmfulness and helpfulness of model outputs. The dataset contains ~160K human-rated examples, where each example in this dataset consists of a pair of responses from a chatbot, one of which is preferred by humans. This dataset provides both capabilities and additional safety protections for our model.

OpenAI WebGPT. The OpenAI WebGPT dataset includes a total of around 20K comparisons where each example comprises a question, a pair of model answers, and metadata. The answers are rated by humans with a preference score.

OpenAI summarization. The OpenAI summarization dataset contains ~93K examples, each example consists of feedback from humans regarding the summarizations generated by a model. Human evaluators chose the superior summary from two options.

When using the open-source datasets, some of the datasets have two responses, corresponding to responses rated as good or bad (Anthropic HH, WebGPT, OpenAI Summarization). We build on prior research by Keskar et al, Liu et al, and Korbak et al, who demonstrate the effectiveness of conditioning language models on human preference markers (such as “a helpful answer” and “an unhelpful answer”) for improved performance. We condition the model on either a positive or negative marker depending on the preference label. We use positive markers for the datasets without human feedback. For evaluation, we prompt models with positive markers.

The Koala model is implemented with JAX/Flax in EasyLM, our open source framework that makes it easy to pre-train, fine-tune, serve, and evaluate various large language models. We train our Koala model on a single Nvidia DGX server with 8 A100 GPUs. It takes 6 hours to complete the training for 2 epochs. On public cloud computing platforms, such a training run typically costs less than $100 with preemptible instances.

Preliminary evaluation

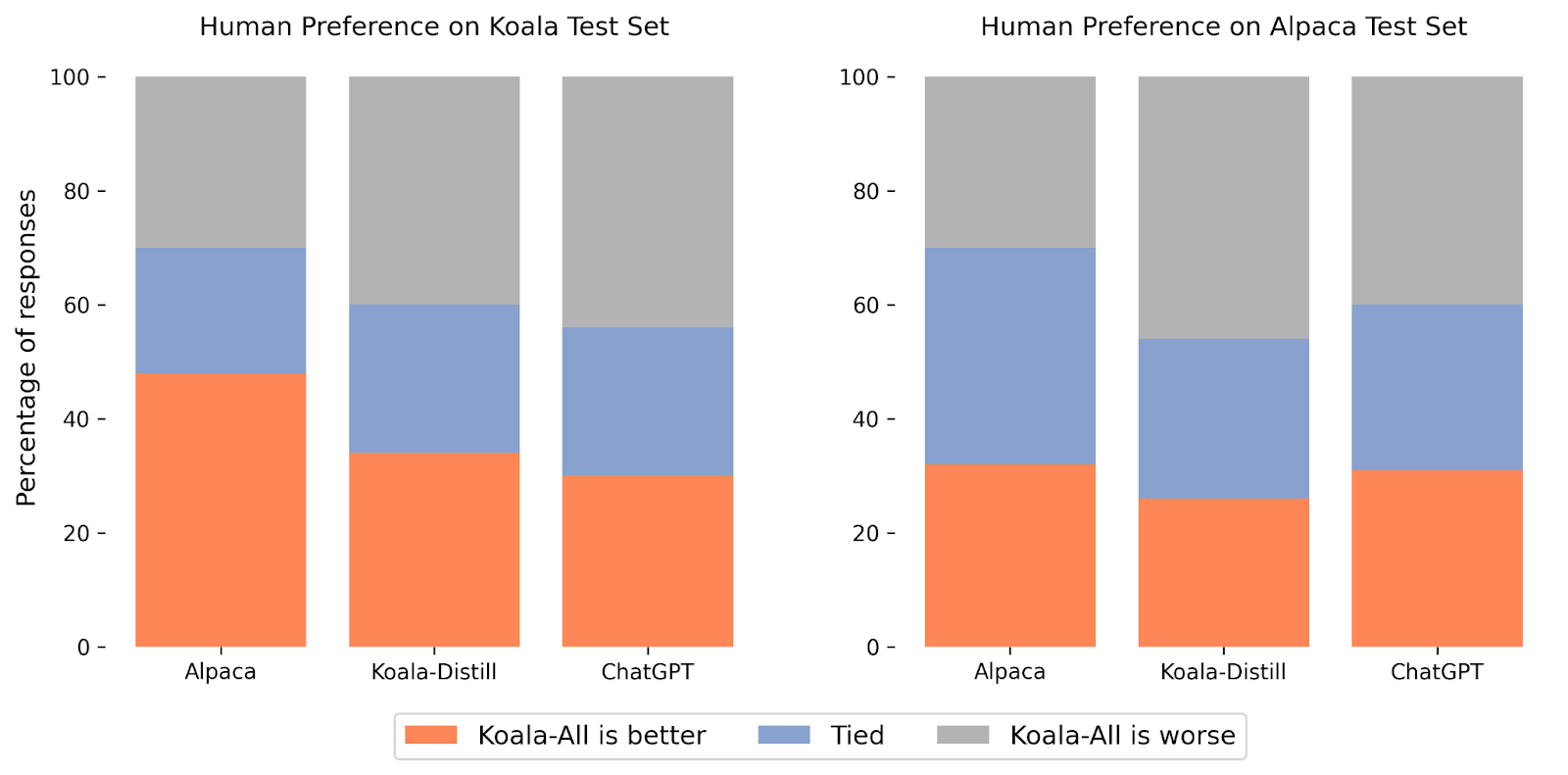

In our experiments, we evaluated two models: Koala-Distill, which solely employs distillation data, and Koala-All, which employs all of the data, including both distillation and open-source data. Our aim is to compare the performance of these models and evaluate the influence of distillation and open-source datasets on final performance. We ran a human evaluation to compare Koala-All with Koala-Distill, Alpaca, and ChatGPT. We present our results in the figure above. We evaluate on two different sets, one consisting of 180 test queries used by Stanford’s Alpaca (“Alpaca Test Set”), and our own test set (“Koala Test Set”).

The Alpaca test set consists of user prompts sampled from the self-instruct dataset, and represents in-distribution data for the Alpaca model. To provide a second more realistic evaluation protocol, we also introduce our own (Koala) test set, which consists of 180 real user queries that were posted online. These user queries span various topics, are generally conversational in style, and are likely more representative of the real-world use cases of chat-based systems. To mitigate possible test-set leakage, we filtered out queries that have a BLEU score greater than 20% with any example from our training set. Additionally, we removed non-English and coding-related prompts, since responses to these queries cannot be reliably reviewed by our pool of raters (crowd workers). We release our test set for academic use and future benchmarking.

With these two evaluation sets, we conducted a blind pairwise comparison by asking approximately 100 evaluators on Amazon Mechanical Turk platform to compare the quality of model outputs on these held-out sets of prompts. In the ratings interface, we present each rater with an input prompt and the output of two models. They are then asked to judge which output is better (or that they are equally good) using criteria related to response quality and correctness.

On the Alpaca test set, Koala-All exhibited comparable performance to Alpaca. However, on our proposed test set, which consists of real user queries, Koala-All was rated as better than Alpaca in nearly half the cases, and either exceeded or tied Alpaca in 70% of the cases. Of course, the more conversational prompts in the Koala test set more closely resemble the Koala training set, so this is perhaps not surprising, but insofar as such prompts more closely resemble likely downstream use cases for such models, this suggests that Koala would be expected to perform better in assistant-like applications. This suggests that data of LLM interactions sourced from examples posted by users on the web is an effective strategy for endowing such models with effective instruction execution capabilities.

Perhaps more surprisingly, we found that training on open-source data in addition to the distillation data (Koala-All) performs slightly worse than training on just ChatGPT distillation data (Koala-Distill), as shown by the comparison to Koala-Distill on both datasets. Though the difference might not be significant, this result suggests that the ChatGPT dialogues are of such high quality that incorporating even twice as much open-source data did not lead to a significant improvement. Our initial hypothesis was that Koala-All should perform at least somewhat better, hence we used it as our primary model in all evaluations, but a potential takeaway from these experiments is that effective instruction and assistant models could be finetuned from LLM backbones such as LLaMA entirely using data from larger and more powerful models, so long as the prompts for these responses are representative of the kinds of prompts that users will provide at test-time. This also further supports the notion that the key to building strong dialogue models may lie more in curating high-quality dialogue data that is diverse in user queries, rather than simply reformatting existing datasets as questions and answers.

Limitations and safety

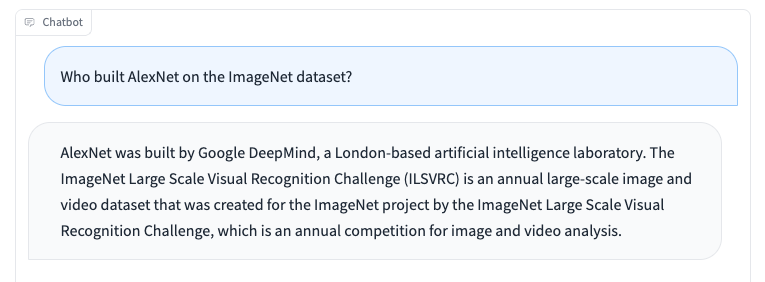

Like other language models, Koala has limitations and can be harmful when misused. We observe that Koala can hallucinate and generate non-factual responses with a highly confident tone, which is likely a result of the dialogue fine-tuning. Perhaps an unfortunate implication of this is that smaller models inherit the confident style of larger language models before they inherit the same level of factuality—if true, this is a limitation that is important to study in future work. When misused, the hallucinated responses from Koala can potentially facilitate the spread of misinformation, spam, and other content.

Koalas can hallucinate inaccurate information in a confident and convincing tone. Beyond hallucinations, Koala shares deficiencies from other chatbot language models. Some of which include:

- Biases and Stereotypes: Our model will inherit biases from the dialogue data it was trained on, possibly perpetuating harmful stereotypes, discrimination, and other harms.

- Lack of Common Sense: While large language models can generate text that appears to be coherent and grammatically correct, they often lack common sense knowledge that humans take for granted. This can lead to nonsensical or inappropriate responses.

- Limited Understanding: Large language models can struggle to understand the context and nuances of a dialogue. They can also have difficulty identifying sarcasm or irony, which can lead to misunderstandings.

To address the safety implications of Koala, we included adversarial prompts in the dataset from ShareGPT and Anthropic HH to make the model more robust and harmless. To further mitigate potential misuse, we deploy OpenAI’s content moderation filter in our online demo to flag and remove unsafe content. We will be cautious about the safety of Koala, and we are committed to perform further safety evaluations of it while also monitoring our interactive demo. Overall, we decided to release Koala because we think its benefits outweigh its risks.

Release

We are releasing the following artifacts:

- An online interactive demo of Koala

- EasyLM: our open source framework we used to train Koala

- The code for preprocessing our training data

- Our test set of queries

- Koala model weights diff against the base LLaMA model

License

The online demo is a research preview intended for academic research only, subject to the model License of LLaMA, Terms of Use of the data generated by OpenAI, and Privacy Practices of ShareGPT. Any other usage of the online demo, including but not limited to commercial usage, is strictly prohibited. Please contact us If you find any potential violations. Our training and inference code is released under the Apache License 2.0.

Future work

We hope that the Koala model will serve as a useful platform for future academic research on large language models: the model is capable enough to exhibit many of the capabilities that we associate with modern LLMs, while being small enough to be finetuned or utilized with more limited compute. Potentially promising directions might include:

- Safety and alignment: Koala allows further study of language model safety and better alignment with human intentions.

- Model bias: Koala enables us to better understand the biases of large language models, the presence of spurious correlations and quality issues in dialogue datasets, and methods to mitigate such biases.

- Understanding large language models: because Koala inference can be performed on relatively inexpensive commodity GPUs, it enables us to better inspect and understand the internals of dialogue language models, making (previously black-box) language models more interpretable.

The team

The Koala model is a joint effort across multiple research groups in the Berkeley Artificial Intelligence Research Lab (BAIR) of UC Berkeley.

Students (alphabetical order):

Xinyang Geng, Arnav Gudibande, Hao Liu, Eric Wallace

Advisors (alphabetical order):

Pieter Abbeel, Sergey Levine, Dawn Song

Acknowledgments

We express our gratitude to Sky Computing Lab at UC Berkeley for providing us with serving backend support. We would like to thank Charlie Snell, Lianmin Zheng, Zhuohan Li, Hao Zhang, Wei-Lin Chiang, Zhanghao Wu, Aviral Kumar and Marwa Abdulhai for discussion and feedback. We would like to thank Tatsunori Hashimoto and Jacob Steinhardt for discussion around limitations and safety. We would also like to thank Yuqing Du and Ritwik Gupta for helping with the BAIR blog. Please check out the blog post from Sky Computing Lab about a concurrent effort on their chatbot, Vicuna.

This article was initially published on the BAIR blog, and appears here with the authors’ permission.

tags: deep dive