ΑΙhub.org

Robots to navigate hiking trails

If you’ve ever gone hiking, you know trails can be challenging and unpredictable. A path that was clear last week might be blocked today by a fallen tree. Poor maintenance, exposed roots, loose rocks, and uneven ground further complicate the terrain, making trails difficult for a robot to navigate autonomously. After a storm, puddles can form, mud can shift, and erosion can reshape the landscape. This was the fundamental challenge in our work: how can a robot perceive, plan, and adapt in real time to safely navigate hiking trails?

Autonomous trail navigation is not just a fun robotics problem; it has potential for real-world impact. In the United States alone, there are over 193,500 miles of trails on federal lands, with many more managed by state and local agencies. Millions of people hike these trails every year.

Robots capable of navigating trails could help with:

- Trail monitoring and maintenance

- Environmental data collection

- Search-and-rescue operations

- Assisting park staff in remote or hazardous areas

Driving off-trail introduces even more uncertainty. From an environmental perspective, leaving the trail can damage vegetation, accelerate erosion, and disturb wildlife. Still, there are moments when staying strictly on the trail is unsafe or impossible. So our question became: how can a robot get from A to B while staying on the trail when possible, and intelligently leaving it when necessary for safety?

Seeing the world two ways: geometry + semantics

Our main contribution is handling uncertainty by combining two complementary ways of understanding and mapping the environment:

- Geometric Terrain Analysis using LiDAR, which tells us about slopes, height changes, and large obstacles.

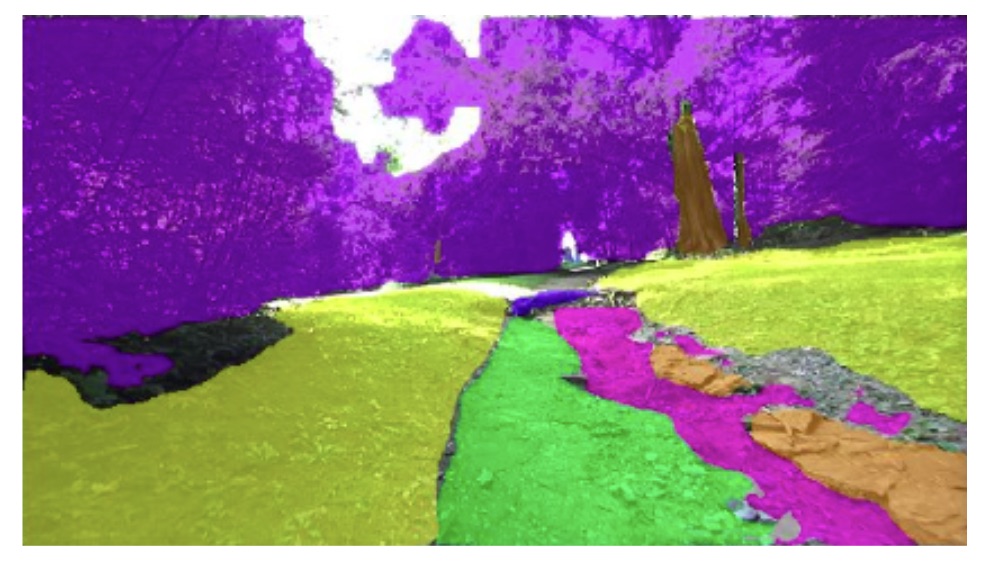

- Semantic-based terrain detection, using the robot camera images, which tells us what the robot is looking at: trail, grass, rocks, tree trunks, roots, potholes, and so on.

Geometry is great for detecting big hazards, but it struggles with small obstacles and terrain that looks geometrically similar, like sand versus firm ground, or shallow puddles versus dry soil, that are dangerous enough to get a robot stuck or damaged. Semantic perception can visually distinguish these cases, especially the trail the robot is meant to follow. However, camera-based systems are sensitive to lighting and visibility, making them unreliable on their own. By fusing geometry and semantics, we obtain a far more robust representation of what is safe to drive on.

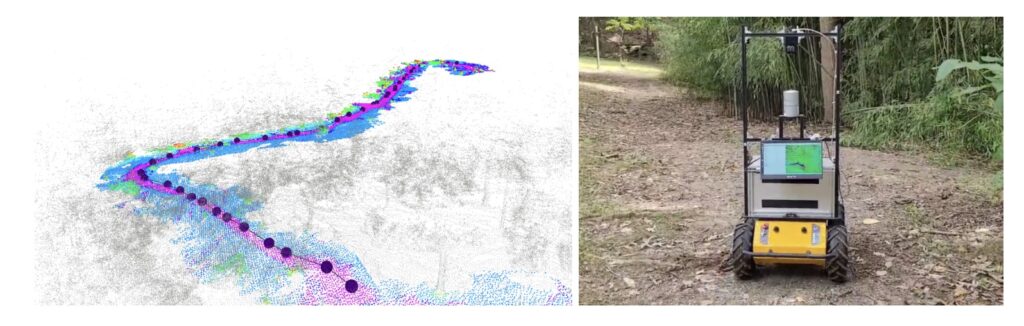

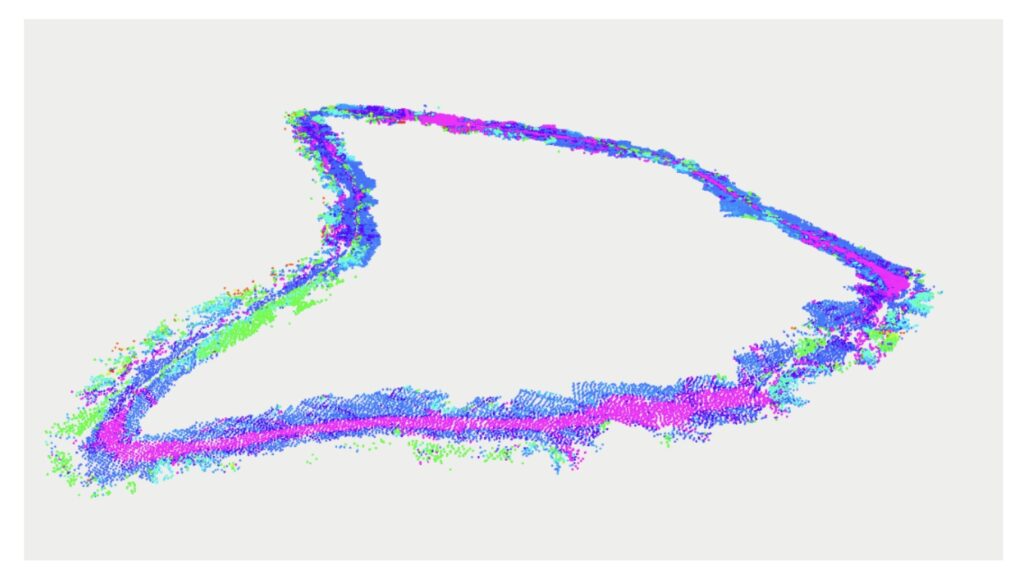

We built a hiking trail dataset, labeling images into eight terrain classes, and trained a semantic segmentation model. Notably, the model became very good at recognizing established trails. These semantic labels were projected into 3D using depth and combined with the LiDAR based geometric terrain analysis map. Using a dual k-d tree structure, we fuse everything into a single traversability map, where each point in space has a cost representing how safe it is to traverse, prioritizing trail terrain.

The next step is deciding where the robot should go next, which we address using a hierarchical planning approach. At the global level, instead of planning a full path in a single pass, the planner operates in a receding-horizon manner, continuously replanning as the robot moves through the environment. We developed a custom RRT* that biases its search toward areas with higher traversability probability and uses the traversability values as its cost function. This makes it effective at generating intermediate waypoints. A local planner then handles motion between waypoints using precomputed arc trajectories and collision avoidance from the traversability and terrain analysis maps.

In practice, this makes the robot prefer staying on the trail, but not stubborn. If the trail ahead is blocked by a hazard, such as a large rock or a steep drop, it can temporarily route through grass or another safe area around the trail and then rejoin it once conditions improve. This behavior turns out to be crucial for real trails, where obstacles are common and rarely marked in advance.

We tested our system at the West Virginia University Core Arboretum using a Clearpath Husky robot. The video below summarizes our approach, showing the robot navigating the trail alongside the geometric traversability map, the semantic map, and the combined representation that ultimately drives planning decisions.

Overall, this work shows that robots do not need perfectly paved roads to navigate effectively. With the right combination of perception and planning, they can handle winding, messy, and unstructured hiking trails.

What is next?

There is still plenty of room for improvement. Expanding the dataset to include different seasons and trail types would increase robustness. Better handling of extreme lighting and weather conditions is another important step. On the planning side, we see opportunities to further optimize how the robot balances trail adherence against efficiency.

If you’re interested in learning more, check out our paper “Autonomous Hiking Trail Navigation via Semantic Segmentation and Geometric Analysis”. We’ve also made our dataset and code open-source. And if you’re an undergraduate student interested in contributing, keep an eye out for summer REU opportunities at West Virginia University, we’re always excited to welcome new people into robotics.

tags: IROS, IROS2025