ΑΙhub.org

Deep learning model trained to identify least green homes

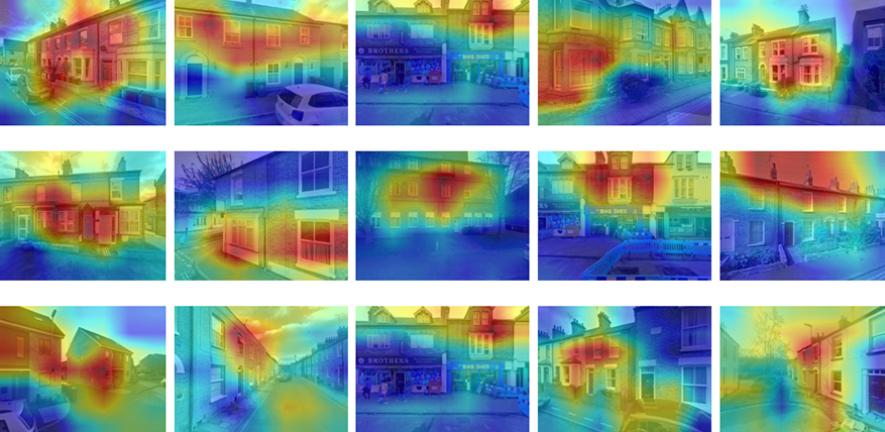

Street view images of houses in Cambridge, UK, identifying building features. Red represents region contributing most to the “Hard-to-decarbonize” identification. Blue represents low contribution. Credit: Ronita Bardhan.

Street view images of houses in Cambridge, UK, identifying building features. Red represents region contributing most to the “Hard-to-decarbonize” identification. Blue represents low contribution. Credit: Ronita Bardhan.

By Tom Almeroth-Williams

“Hard-to-decarbonize” (HtD) houses are responsible for over a quarter of all direct housing emissions – a major obstacle to achieving net zero – but are rarely identified or targeted for improvement.

Now a new deep-learning model trained by researchers from Cambridge University’s Department of Architecture promises to make it far easier, faster and cheaper to identify these high priority problem properties and develop strategies to improve their green credentials.

Houses can be hard to decarbonize for various reasons including their age, structure, location, social-economic barriers and availability of data. Policymakers have tended to focus mostly on generic buildings or specific hard-to-decarbonise technologies but the study, published in the journal Sustainable Cities and Society, could help to change this.

Maoran Sun, an urban researcher and data scientist, and his PhD supervisor Dr Ronita Bardhan (Selwyn College), who leads Cambridge’s Sustainable Design Group, show that their AI model can classify HtD houses with 90% precision and expect this to rise as they add more data, work which is already underway.

Dr Bardhan said: “This is the first time that AI has been trained to identify hard-to-decarbonize buildings using open source data to achieve this.

“Policymakers need to know how many houses they have to decarbonize, but they often lack the resources to perform detail audits on every house. Our model can direct them to high priority houses, saving them precious time and resources.”

The model also helps authorities to understand the geographical distribution of HtD houses, enabling them to efficiently target and deploy interventions efficiently.

The researchers trained their AI model using data for their home city of Cambridge, in the United Kingdom. They fed in data from Energy Performance Certificates (EPCs) as well as data from street view images, aerial view images, land surface temperature and building stock. In total, their model identified 700 HtD houses and 635 non-HtD houses. All of the data used was open source.

Maoran Sun said: “We trained our model using the limited EPC data which was available. Now the model can predict for the city’s other houses without the need for any EPC data.”

Bardhan added: “This data is available freely and our model can even be used in countries where datasets are very patchy. The framework enables users to feed in multi-source datasets for identification of HtD houses.”

Sun and Bardhan are now working on an even more advanced framework which will bring additional data layers relating to factors including energy use, poverty levels and thermal images of building facades. They expect this to increase the model’s accuracy but also to provide even more detailed information.

The model is already capable of identifying specific parts of buildings, such as roofs and windows, which are losing most heat, and whether a building is old or modern. But the researchers are confident they can significantly increase detail and accuracy.

They are already training AI models based on other UK cities using thermal images of buildings, and are collaborating with a space products-based organisation to benefit from higher resolution thermal images from new satellites. Bardhan has been part of the NSIP – UK Space Agency program where she collaborated with the Department of Astronomy and Cambridge Zero on using high resolution thermal infrared space telescopes for globally monitoring the energy efficiency of buildings.

Sun said: “Our models will increasingly help residents and authorities to target retrofitting interventions to particular building features like walls, windows and other elements.”

Bardhan explains that, until now, decarbonization policy decisions have been based on evidence derived from limited datasets, but is optimistic about AI’s power to change this.

“We can now deal with far larger datasets. Moving forward with climate change, we need adaptation strategies based on evidence of the kind provided by our model. Even very simple street view photographs can offer a wealth of information without putting anyone at risk.”

The researchers argue that by making data more visible and accessible to the public, it will become much easier to build consensus around efforts to achieve net zero.

“Empowering people with their own data makes it much easier for them to negotiate for support,” Bardhan said.

She added: “There is a lot of talk about the need for specialised skills to achieve decarbonisation but these are simple data sets and we can make this model very user friendly and accessible for the authorities and individual residents.”

Cambridge as a study site

Cambridge is an atypical city but informative site on which to base the initial model. Bardhan notes that Cambridge is relatively affluent meaning that there is a greater willingness and financial ability to decarbonise houses.

“Cambridge isn’t ‘hard to reach’ for decarbonisation in that sense,” Bardhan said. “But the city’s housing stock is quite old and building bylaws prevent retrofitting and the use of modern materials in some of the more historically important properties. So it faces interesting challenges.”

The researchers will discuss their findings with Cambridge City Council. Bardhan previously worked with the Council to assess council houses for heat loss. They will also continue to work with colleagues at Cambridge Zero and the University’s Decarbonisation Network.

Read the research in full

Identifying Hard-to-Decarbonize houses from multi-source data in Cambridge, UK, Maoran Sun and Ronita Bardhan, Sustainable Cities and Society (2023).

tags: Focus on sustainable cities and communities, Focus on UN SDGs